At Intel’s recent developer forum, the company announced a partnership with Google that would put the microchip maker’s RealSense 3D scanner to use for the Google Tango mapping project.

Many tech sources are calling the partnership a perfect match, since Intel’s RealSense cameras are sophisticated consumer devices for 3D scanning, and Google’s Tango sensors are adept at performing the complementary tasks of 3D-mapping and object tracking. Put together into a single device, these two sensor packages would be a powerful match.

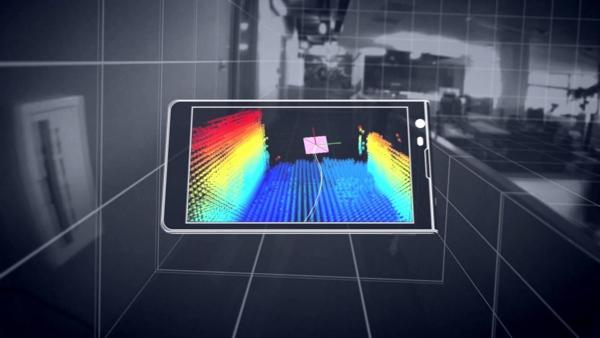

The first fruit of the partnership will be a developer’s kit for a Project Tango smartphone. The phone looks to have a screen of about 6 inches (putting it squarely in the too-big-for-this-reporter territory) and a collection of sensors on the back comprising the RealSense 3D camera package. These sensors include Intel’s RealSense R200 camera for depth-sensing and a number of RGB cameras and infrared cameras for texture and alignment.

The developer’s kit is expected to be available by the end of the year. This kit, which will allow developers to try the technology pairing out and create software that exploits it, will be the first step toward making an Intel/Google Tango device into a fully featured consumer product.

The last time we saw Google announcing a smartphone scanner, it included a Qualcomm scanner that used an active time-of-flight camera to gauge depth. In contrast, Intel’s RealSense camera uses passive light-field technology. In an article earlier in the year describing Intel’s RealSense cameras, SPAR explained light field technology as “using a main lens accompanied by an array of microlenses positioned to capture depth information.”

Engadget, who was able to try out the Tango developer’s kit, reports that the device allows users “to scan 3D objects and offer three-dimensional portrayals of the environment in real-time.” They also report that the motion tracking capabilities offer the potential for games. They explain that an Intel spokesperson “showed us a cube stacking demo, where he could create virtual walls and barrier overlaid atop the real-world environment — sort of like an augmented reality Minecraft, if you will.”

It will be some time before the device is in the hands of consumers, and most of the first available applications will likely be designed for gaming. As a result, it remains to be seen what uses the more exacting geospatial professionals may find for the technology.

Regardless, this partnership appears to be a big step toward the mainstream for 3D-imaging technology.