High on the want list for new 3D capture technologies is speed. Yes, I know, most of you mean you’d like lidar that will increase the speed of your workflow, but imagine what you could do if the lidar sensor itself actually scanned faster as well. What if it scanned fast enough to capture precise measurements of a speeding bullet? Such a sensor would have some obvious uses—robotics, self-driving vehicles, drones—but what else could we use it for?

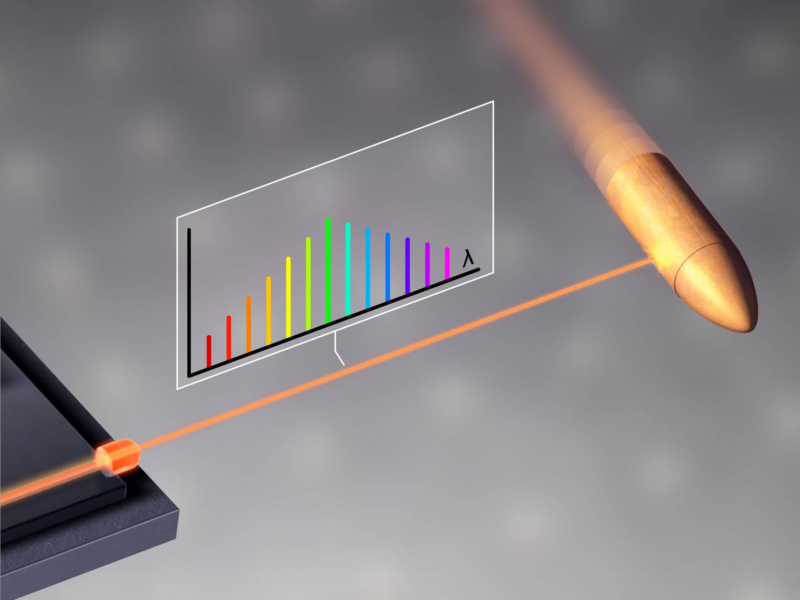

These are the questions we will have to start asking soon. As reported in this excellent piece on Physic World, researchers from Germany’s Karlsruhe Institute of Technology and Lausanne Switzerland’s Federal Institute of Technology have made an ultra-speedy lidar a reality. The team recently published research in Science claiming that they have achieved the “fastest distance measurement so far demonstrated.”

In testing, the researchers fired a bullet (moving 150 meters per second) aimed the lidar at its trajectory, and managed to generate a good 3D image of the bullet. According to KIT, they hit “micrometer” accuracy and gathered 100 million distance measurements per second.”

How it works

The technology sounds more than a little complex in operation. Rather than using photons to measure, scientists used solitons, which Physics World describes as “wave packets of laser light that maintain their shape as they propagate.”

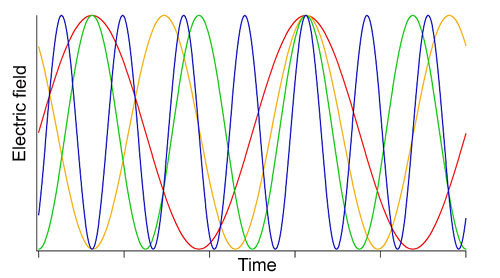

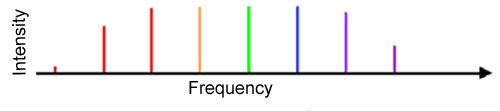

A simplified graphic demonstrating the wavelengths in a “comb”. Credit: NIST

The scientists use these solitons in the form of optical frequency combs, which our buddies over at NIST helpfully explain as a sequence of quick, closely spaced laser pulses containing “a million different colors.”

How does that sequence resemble a “comb”? When you convert the optical properties of these pulses to frequency numbers, you can chart the wavelengths in a simplified form that looks like a comb with evenly spaced teeth. Until now, NIST says these combs have been used in metrology labs, and for physics research measuring “lasers, atoms, starts, or other objects with extraordinarily high precision.”

An even more simplified graphic demonstrating the wavelengths in a “comb”. Credit: NIST

Now, of course, we’re using them to measure… the shape of bullets, because the scientists deduced that one comb reflecting off of a moving object would interfere with another new comb. Physics World lays it out: Since the structure of the comb is a given, scientists are able to take the phase difference of the superimposed teeth to calculate the distance traveled by the first comb.

TL;DR: It uses fancy interferometry.

Limits

No report of a technological breakthrough would be complete before discussing the system’s challenges. It’s large, it can only scan a meter away, and it generates a ton of data. Ultimately, the team is hoping the system can be small enough to fit in a matchbox, at which point the other two problems may not seem like such a big deal.

For more information—and to get your physics fix—check out the original research in Science, or the excellent reporting in Physics World, which digs deeper into the materials used to generate the combs.