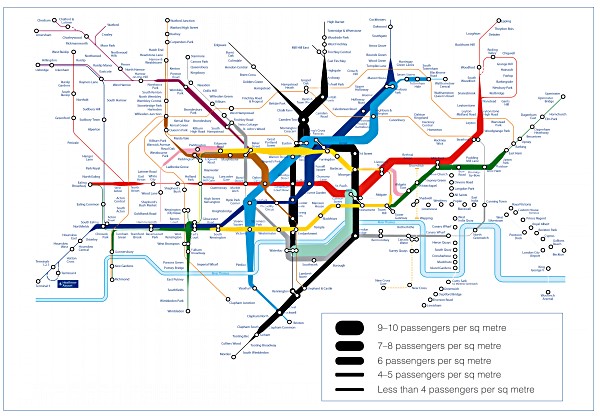

If you’ve ever used public transport in London, you will be aware that there is a need to increase the capacity of the city’s public transport infrastructure. Just looking at my employer, London Underground, the numbers are quite staggering. The tube carries over 1 billion passengers a year, with up to 4 million journeys made per day. So it is no wonder that during peak times the trains and platforms are very busy.

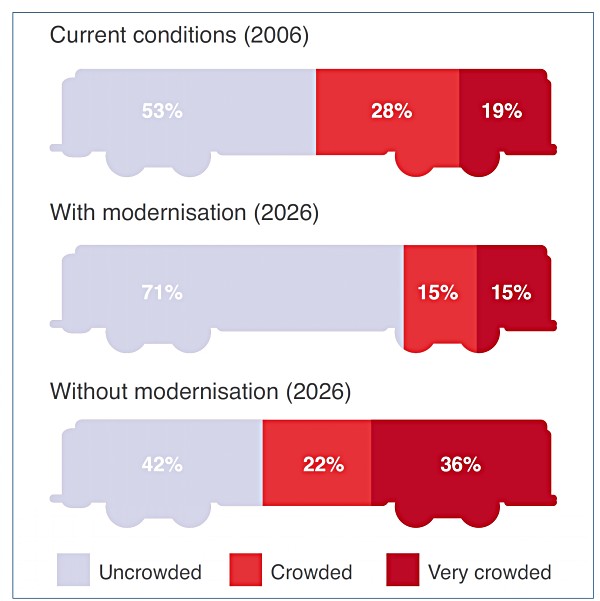

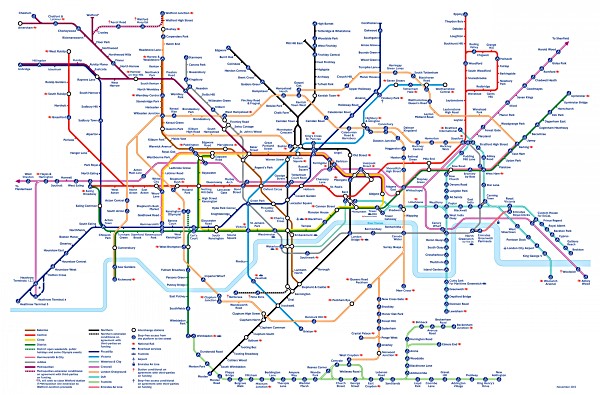

Though ongoing improvements are being made, and there has been a tangible improvement to the reliability and comfort of my journeys, if the system is not drastically improved there will be trouble ahead and the improvements will be for nothing. By 2026 it is forecast that during the morning rush hour there will be twice as many passengers as there currently are. Clearly there is a need for continued and extended modernisation, as demonstrated by Figure 1and Figure 2.

Figure 1 – Crowding Levels of Cars without Tube Modernisation, 8-9am, 2026

Figure 2 – Proportion of Passengers Experiencing Crowding, 8-9am, 2026

In London Underground there are numerous projects to cope with the increasing amounts of passengers. Some of these are “obvious” major works at key interchange stations to allow for larger numbers of passengers to circulate by adding new corridors or such like. Other projects are undertaken to move the passengers faster and thus increase capacity. This is done in a number of more complex ways by upgrading the signalling across an entire line or rolling out new train stock.

Stations

One thing that all upgrades have in common, of course, is that survey work has to be carried out first to understand existing geometry conditions and locations of assets. In tunnels between stations, this information is easy to capture and present in an understandable way. We use a variety of methods to do this, including traditional total station work, aerial photography for open sections that are not underground, mobile-trolley-mounted kinematic laser scanning and, occasionally, tripod-based terrestrial laser scanning.

With complex stations that have many different lines stopping at them, it is far more difficult to capture and present the data in an understandable way. Our default way of surveying such scenarios has now become terrestrial laser scanning.

Figure 3 – Point clouds of Existing Stations

.1.jpg)

Crossrail

One of the schemes that will have the greatest impact on congestion relief is Europe’s largest construction project, the major £15 billion Crossrail project. This project is creating an entire new high-speed tunnel from West to East that interfaces with key congestion points. (It was whilst watching a fantastic BBC documentary on this project that I got that idea for this blog.)

Figure 4 – Crossrail Route (Purple Line East to West)

Figure 5 – New Crossrail Canary Wharf Station

One of the many interesting parts of the program was the modification of an existing disused tunnel to include as part of the new route. This presented the project team with many challenging situations, since they did not know the definitive construction of the tunnel from 130 years ago. Parts of the tunnel were found at the last minute to be a different size than the team had previously thought when completing the design. As a result, it was necessary for them to find new engineering solutions under pressure while on site. It was not only the geometry of 130 years ago that caused problems, it was the way that 130 years of pressure on a brick arch tunnel significantly strengthened the tunnel more than expected, as this made breaking it out take far longer than the project schedule allowed for.

After a timely blog post number 100 from Sam Billingsley about archiving of data, I thought: What can we do now to ensure a similar problem is not faced 130 years from now?

With the vast majority of design for major projects now being done in 3D, we have a very good start to ensure the intended geometry is documented. But, without a proper post-construction as-built survey being recorded as well, are we really more prepared for the future than we were 130 years ago? What of the construction material? The material should be documented in the design BIM, but is land surveying the right discipline to record what was actually used on site as part of an as built? Even if everything is recorded 100% at the end of construction, are we sure that the formats we archive will be useable in 130 years time?

These however, are all thoughts for a future blog post.