In the early aftermath of the fire at Paris’ historic Notre Dame cathedral last month, you surely saw one of the many stories about how 3D laser scanning might very well be useful in the inevitable restoration work. This is obviously great exposure for the 3D data capture industry.

Andrew Tallon with his Leica scanner, from the 2015 National Geographic special.

If not, here’s the nickel round-up (Jonathan Barnes dives deeper for SPAR here): Vassar College art history professor Andrew Tallon laser scanned the entirety of the structure (or as much of it as you can get with about 50 scan stations) as part of documentation efforts he undertook in 2010, which led in part to a book he co-authored and published in 2013 and a National Geographic special, among other things, in 2015. Tragically, Tallon died of brain cancer in 2018 at the age of 49.

There’s a nice local angle piece in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, noting that Tallon went to Shorewood High School in Shorewood, Wisconsin, and was fascinated by Notre Dame as far back as the third grade. They interviewed his mother. Go local journalism!

However, much of the coverage is pretty theoretical: Hey, a 3D replica of the cathedral exists. That will probably be helpful! But how might that actually work?

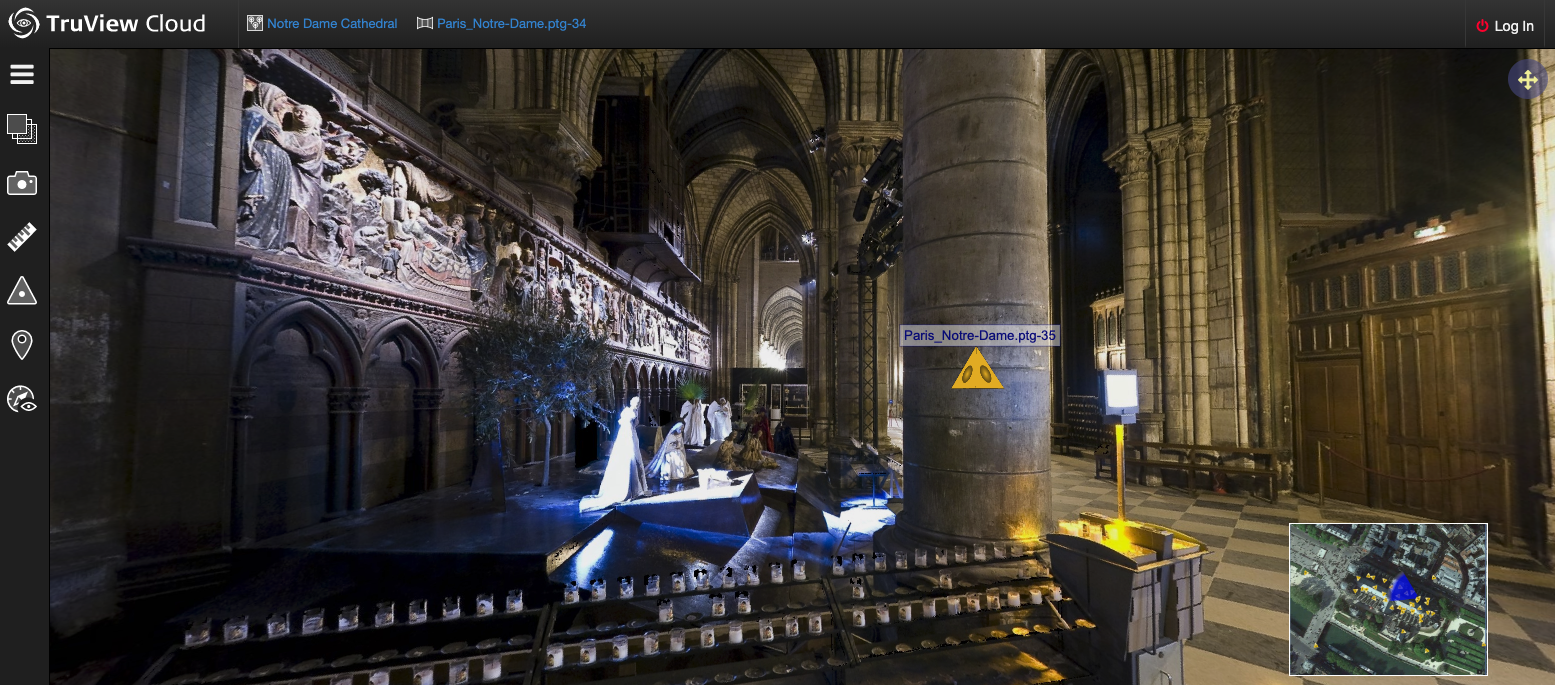

Well, first and foremost, the scans can help people tour the space virtually, since they can’t get in there physically right now. Kudos to Leica for quickly getting a TruView of Notre Dame set up for public consumption. Click on the image below to play around with the 41 positions they’ve uploaded:

While I’m personally lucky enough to have walked those floors in January of 2018, there are obviously countless others who didn’t get the opportunity and may not for quite some time. You can get a feel for the kind of virtual experience they might set up by taking a tour of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West property here. This is a chance not only to extend access to the physical facility, but also to keep its historical value top of mind as fundraising efforts continue and work eventually begins (though it has been noted the Catholic Church is generally not known for its lack of cash).

While I’m personally lucky enough to have walked those floors in January of 2018, there are obviously countless others who didn’t get the opportunity and may not for quite some time. You can get a feel for the kind of virtual experience they might set up by taking a tour of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West property here. This is a chance not only to extend access to the physical facility, but also to keep its historical value top of mind as fundraising efforts continue and work eventually begins (though it has been noted the Catholic Church is generally not known for its lack of cash).

How might that work actually begin? Quite possibly with another set of scans. By creating a second point cloud with which to compare against Tallon’s originals, those leading the reconstruction effort will have a delta showing the exact extent of the damage. Just exactly what was lost? What moved? What portions of the structure might be most precarious? This would obviously help with initial engineering.

This isn’t brand-new territory

Obviously, this won’t be the first time 3D data has been used as part of restoration work. “My very first scan job way back in the very early 2000s was to scan the starboard side of an old wooden tall ship so a replica of it could be made in a movie studio,” said Michael Harvey, senior product manager for reality capture at Leica Geosystems.

In this particular situation, a product like the Hexagon 3DReshaper can compare cloud to cloud and might be a starting point. “The challenge with that is the site is very large and this type of tool will only give restoration professionals a place where possible change could have taken place,” he said. “If anyone did any type of renovating or re-decorating [since 2010], this type of change detection would also highlight those areas.”

Harvey said this is a common scenario where a construction team might check what’s being built against a model, “as well as in forensic applications in both fire and pre- and post-blast investigations. Deformation monitoring is also a popular use for this approach.”

Further, while they might used the scan data in similar fashion to that old wooden tall ship, “it could also be used for calculating amounts of material,” said Harvey, or for determining “the orientation of both structural and artistic elements. And we are only thinking of the actual point cloud here. With laser scanning, you also get a rich image set of the data to accompany the point cloud. So, along with structural components, or count and placement of masonry, we have the benefit of the image to restore the color of all the elements as well. By combining the spatial information with the images, we have a digital replica of what it was on the day it was captured, thus making a full restoration very possible.”

Of course, there is some question as to where exactly the scan data is and who has ownership of it. The second-to-last paragraph of the Atlantic article that talks about the scanning work is quite the cliffhanger:

But as the cathedral officials and architectural authorities in France and around the world begin to consider what to do, they will come looking for the laser-data files that Tallon created. Blaer estimated that, despite the high resolution of the scans and panoramic photographs, the files would be roughly a terabyte, small enough to fit on a single hard drive, but unlikely to be stored in the cloud. All those data now exist on a single disk, a tiny portal into the past, which is sitting somewhere on Earth. Blaer thought it might be in the hands of Tallon’s students at Vassar. But Ochsendorf thought the data were most likely with the rest of Tallon’s archive, in the possession of his widow, Marie, who held Andrew in her arms as he died.

At the moment, we only have the TruViews. “The set I have seen is only a subset,” Harvey said. “The good thing is that 3D data is always available. Users can export the data into binary formats that can always be imported into newer versions of the software. Furthermore, I still access data that I personally collected over 15 years ago and it is just as useful now as it was then. With formats like the new LGS file as well as the e57 standards, 3D data will be well preserved for future uses.”

This reporter was unable over a couple of days to track down where the data might actually be, but we’ll assume that’s a hurdle restoration experts can overcome. It will likely be a long and expensive process, with painstaking care taken to ensure nothing of immeasurable value is damaged along the way. It’s a high-pressure situation, no doubt, for anyone taking on the work.

Hopefully, however, it goes relatively smoothly and the 3D data is of considerable service. I’d hate to think of what future travelers might miss out on. Each of my three trips there have been memorable, indeed (even if the line was too long for me to bother to go inside the first two times!).