All around the world, the effects of climate change are front-of-mind for governments and scientists trying to mitigate negative consequences for life on Earth. Different parts of the planet are affected in different ways, but nearly every corner is touched in one way or another. In order to maximize protection against these effects, it’s important to have a clear idea of the changes that are actually taking place. To do that, in turn, we need to have reliable data to properly monitor these trends.

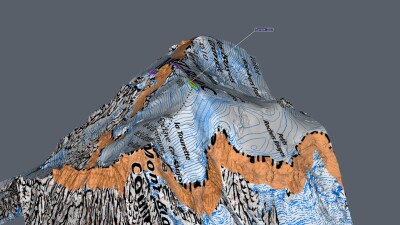

It’s easier to obtain retroactive data for some of these areas than others, and one particularly interesting area of tracking where that retroactive data has not been available is surveying the summits of mountains. In France, a team of surveyors has been working to rectify that for Mont Blanc, the highest peak in Western Europe. Every two years since 2001 (save for one missed trip during the COVID-19 pandemic), a team of surveyors - including employees from Leica Geosystems, part of Hexagon, and members of the Land Surveyors of France - have ascended to the summit of Mont Blanc to measure the altitude of the peak and model the mountain’s ice cap.

Recently, Geo Week News spoke to Farouk Kadded, a product and technical support team manager for Leica Geosystems, about the evolution of the project and some of the findings from the team’s survey earlier this year.

Kadded holds a unique position within this project, as he’s been a part of each ascension and survey since the first iteration in 2001. He tells Geo Week News that the Land Surveyors of France originally reached out to Leica in 2001 to ask if it could provide GNSS hardware, and he volunteered when the company asked if anyone wanted to participate. Kadded, who lives in France, is an experienced mountaineer and had climbed Mont Blanc prior to this.

“I do a lot of mountaineering all around the year, skiing and climbing,” Kadded said. “So I have a lot of experience and background in mountaineering. I have also done all of these measurements on Mont Blanc. So I know the mountain, I know the climbing, I know all the different parameters of the mountain. So it was a good opportunity for me to say, Yes, I want to try.”

Kadded was able to speak about how exactly these measurements are taken, and interestingly how things have changed since the beginning. Those changes range from simply the number of people who take part in the mission – up to 22 in the most recent trip in 2023 compared to fewer than 10 in the initial treks – along with the amount of time the trip takes.

“In the beginning, we climb only for two or three days, because we did not plan any preparation, any acclimatization, etc., just the climbing to the first refuge and then to the summit,” Kadded explained. “Normally, Mont Blanc takes only two days, but after several measurements we increased the preparation to have a better acclimatization.”

Kadded went on to explain that now they spend more time on the mountain acclimating to the conditions, because there is preparation needed to be at such a high altitude. (Mont Blanc’s peak is nearly 5,000 meters, or over 15,000 feet.) Today, they spend about a week on the mountain to better acclimate with the conditions in order to more easily complete the surveying.

On top of the number of people and the time involved, as one would expect the technology used in the project has changed over the years as well. Kadded notes that in the most recent expedition they utilized the GS18 I, a GNSS RTK rover from Leica Geosystems in which the “I” is for imagery. They are now able to capture imagery from the summit and the ice cap with this technology, and are able to do real-time measurement of the ice cap. On top of that, Kadded says, the big change is the number of satellites available for measurement.

“At the beginning, we measured only with GPS satellites. Now we can also use the GLONASS Russian satellites, and the European satellite, Galileo, and Chinese satellites,” he told Geo Week News. “Now we have around 30 satellites on the summit, so we can do the measurement of Mont Blanc during the entire day without any specific short windows to measure. At the beginning, we had to plan when we had the minimum [number of] satellites during the day. Sometimes it was early in the morning, sometimes in the afternoon.”

As far as the results, Kadded notes that they have found changes in the survey results which are likely a consequence from this past summer, which was the hottest on record worldwide and which featured extreme heat waves throughout Europe. He says that they actually have more recently begun measuring at the beginning and end of the summer to compare those two surveys, and contrary to what most would assume the altitude typically increases during the summer months. However, this year, they had approximately “the same measurements.”

Kadded says that is because of increased wind on the summit during the summer months, and the heat. “We had more than 10 days around 10 degrees on the summit. Normally, at the summit, it’s always zero, but this summer has had a lot of increasing of temperatures.”

These findings are why it’s so important to take these measurements. Kadded notes, “If we want to have any conclusions, it’s important to have a lot of data. You need to have more than 50 years [of data], and it’s important to measure regularly and accurately in the same way. For 22 years now, we measure regularly every two years, and we have a small database at the moment. We want to increase this database in the next 10, 20 years.”

This mission will continue over the coming years, with the next ascension set to take place in the summer of 2025. And Kadded says that, beyond the actual work, it’s important to also note the connection of the people involved in the project.

“You spend one week with people, you spend a lot of time with them, sleeping and climbing, and you create a link. To reach the summit and just take a photo and go back, it’s quite easy. But to stay on the summit, around 5000 meters, it’s not the same job. It’s really important to organize, to train, and to motivate people.”