“I must have done something wrong.” This is what went through the mind of Dr. Kim Calders, one of a group of scientists who recently published a paper in the British Ecological Society journal detailing their use of laser scanning to estimate biomass of trees in the Wytham Woods in the United Kingdom. The results of their scanning, and subsequent data processing and calculations, were the revelation that previous biomass carbon estimates in this forest, and perhaps others like it, were much lower than the actual levels. Calders took a few minutes after the paper’s publication to speak with Geo Week News about the team’s data collection processes and what the results could mean.

Before delving into Calders’ teams’ methodology, it’s worth quickly discussing the allometric models that have been a mainstay in these types of calculations prior to this. Allometry, which is used for all kinds of living things and not just trees, at its most basic level is a way of measuring how living things’ characteristics change with size. For trees specifically, this process requires trees to be cut down to measure diameter, and once a biomass is calculated the number is scaled up or down for other trees depending on size. The issue is that this work is most easily done on smaller trees, and the complexities of trees – they grow more slowly than most living things, and processes like coppicing lead to unique changes in individual trees – lead to inconsistencies, particularly for larger trees.

That brings us back to the project undertaken by Calders and the rest of the team – which included Bob Bunce, the scientist who first created the highly influential allometric models created in the 1960s, who sadly passed away in 2022 – to use terrestrial laser scanners to capture the Wytham Woods outside of Oxford. In our conversation, Calders was sure to emphasize that the results, which conclude previous calculations may have underestimated the carbon biomass of the Wytham Woods by as much as 77 percent, are not without uncertainty. Even so, this level of difference is large enough to be significant even with maximum error bars on both calculations, and there are real potential ramifications.

In thinking about the process undertaken by this group of scientists, the choice of Wytham Woods is a logical place to start. Calders is careful to avoid putting too much emphasis on this location as some universal signifier that can be carried over to the rest of the world, or even Europe. Instead, this area was chosen largely because it is prepared for this kind of research. It’s owned by Oxford University and is equipped with “a lot of infrastructure,” including a flux tower. That said, another UK-based ecologist and forestry expert, Keith Kirby, found in an analysis of UK woodlands that Wytham fits right within the averages for several different measurements. Again, that’s not to say these results can be copied and pasted throughout the UK, but it’s as good a place to conduct this type of study as any in the area.

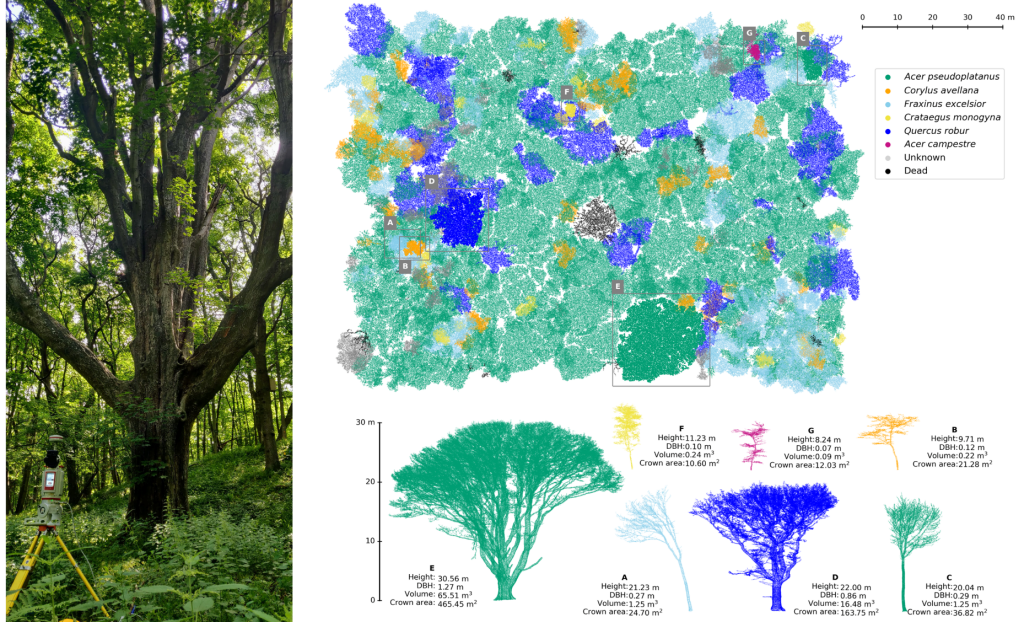

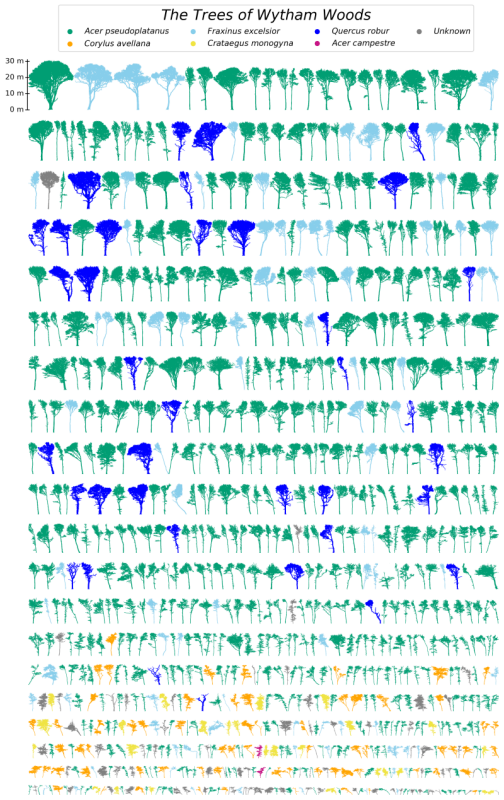

As Calders notes in our conversation, the actual process for scanning the trees and then processing and analyzing the data wasn’t exactly novel, as this kind of work has been done for a variety of applications for many years. In fact, Calders himself had been doing this type of forestry scanning work since 2010. The team used a RIEGL VZ-400 terrestrial laser scanner and captured the trees during their leaf-off phase, which allowed trees to be easily and fully captured without having to utilize UAVs and also, crucially, required significantly less data manipulation which could cloud any results. From there, point clouds were acquired and segmented to get individual trees, from which biomass could be calculated using models detailed in the group’s paper linked above.

The results of the work, presenting evidence that Wytham Woods in particular, and potentially other similar forests in the UK, could contain significantly more carbon than previously thought, could have real ramifications. Specifically, it heightens the already-present knowledge that preserving these forests is a crucial piece of reaching worldwide carbon goals. As Calders notes, some of this is around deforestation, which is not to say no trees should be cut down, but rather that care needs to be taken when doing so, particularly in preserving older and larger trees.

Additionally, this is also more support for placing a greater emphasis on counteracting more natural disturbances like invasive species of bugs and fungi, which are issues throughout Europe and other parts of the world. When trees are lost to these disturbances, the stored CO2 is eventually released back into the atmosphere. These numbers should also heighten the work being done around afforestation, ensuring that new trees are not only being planted, but cared for after to ensure they continue to grow and mature.

Ultimately, Calders says towards the close of the conversation, this isn’t new information. It’s no secret that trees store carbon, and that bigger trees store more. “Nothing has changed for Wytham Woods,” Calders says. “It’s not like last week there was this much carbon, but then this week this paper came out.”

However, having a more accurate picture of just how much carbon is being stored, particularly if it’s more than previously believed, is crucial as societies around the globe are fighting climate change and looking to offset carbon emissions. Laser scanners can be a key piece in getting those accurate calculations. It’s likely that other forests around the world won’t have quite the disparity in biomass between this methodology and allometric models, but given that we have the tools to figure this out for sure it only makes sense we make the most of them. To that end, Calders and his team are starting to do more of these scans around the UK, with plans to do more in Germany, Belgium, and France, but also several tropical countries.