One of the more provocative keynotes at SPAR 3D 2016 was delivered by Paul Davies, an associate technical fellow at Boeing who discussed the past, present, and future of augmented reality (AR) technology in the manufacturing space (and, by proxy, the 3D technology space in general).

The key takeaway? It’s already capable of amazing things, but don’t let that fool you into thinking AR is ready for commercial use.

First, what he means by AR

Paul Davies of Boeing presents at SPAR 3D 2016.

Given all the hype about AR, VR, MR, and all the other R’s, I was glad to hear Davies lay out a very precise definition of augmented reality at the beginning of this talk. When you use AR technology, he explains, “part of what you see is real, and part of what you see is computer generated.”

Google glass may seem like AR, he explained, but it’s really more like a heads-up display, since it projects information over your view of the real world. Augmented reality presents digital information to you as if it actually exists in the real world. It captures the world with a camera, and makes the content line up with objects in the real world.

A quick history of Boeing and AR

Davies detailed Boeing’s history with AR going back to the late 80’s. He showed a picture from their wiring shop (see top of the article), where a Boeing researcher was using a headset device that showed a set of 2D directions for how to lay out wires in a very complex electrical wiring harness.

Davies said this might have been the first industrial implementation of augmented reality—and even the use-case that gave the technology its name.

A slow move across the Gartner curve

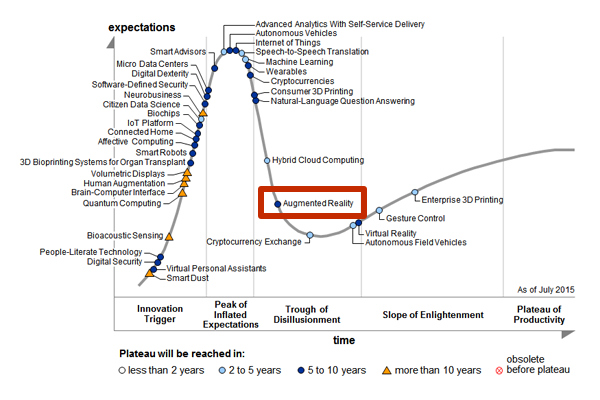

More than a decade after its first appearance, AR still hasn’t progressed very far on the Gartner curve.

In talking about how the technology has developed over the past few years, Davies referred to the Gartner hype cycle curve. “This is the curve that helps us understand where technologies are from when they first pop up on peoples’ radar to when they actually become useful in industry,” he said.

In 2004, almost two decades after Boeing first used an AR solution in their wiring shop, AR first shows up on the curve. Gartner puts the technology way to the left and gives the AR dot a color indicating that it has more than 10 years before it reaches maturity. After showing us this curve, Davies showed the audience year after year, with the technology slowly moving along the curve—very, very slowly.

Unlike certain technologies that zip along the curve, augmented reality is still in the process of maturing more than a decade after it first appeared. Though Gartner had guessed in 2004 that AR would be ready by 2014, their prediction in 2015 said it would be another decade still before it’s ready.

There are a number of reasons for this, “and it really highlights the disparity between what people expect—the media hype around something—and the reality of what we can actually do today.” In other words, AR is popular, it’s a cultural phenomenon, but it’s not ready for industry.

What AR can do already

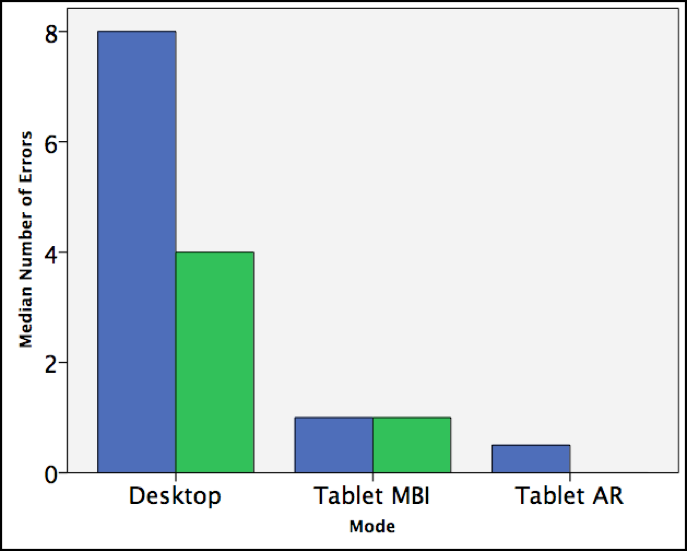

Boeing chart showing increase in worker productivity when using AR

When you see what AR can do today, it’s hard to imagine that it hasn’t yet reached maturity.

Davies presented on Boeing’s already famous study that showed how augmented reality helps people to perform complex tasks, even when those people have no previous experience. For this study, Boeing gave test subjects a tablet loaded with augmented reality directions for airplane wing assembly. Their performance in that task was compared to the performance of subjects who had access to PDF directions displayed on a computer, and subjects who had PDF instructions displayed on a tablet.

The results? The AR group was 30% faster and 90% more accurate on their first try. By the second try, errors had been reduced to virtually zero. “With augmented reality,” Davies said, “people were almost expert even though they had never seen the wing before.”

Why AR STILL isn’t ready

Remember, this previous experiment used AR on a tablet. Giving someone AR directions on a headset, like in this popular (and speculative) AR video produced by BMW in 2007, is still impossible.

As Davies explained, there are three building blocks to AR, two of which we haven’t figured out yet.

- Tracking — Understanding the 3D pose of a camera as well as the position of real objects in 3D space with a high degree of accuracy.

- Core function — A software component that ties in information and functions like CAD models, calibration data, user interface, and rendering.

- Visualization — How you present that augmented view to the user.

“Tracking and visualization are the two blocks that I don’t consider to be solved,” Davies said. For visualization, he said, the issue is often that you have to hold something, like a cell phone or a table. We still haven’t worked out the ergonomics of making AR devices wearable and safe within the dangerous environments where we want to use them.

As far as the tracking problem, the issue is that we’re still using external infrared systems to help locate AR devices in space. “IMUs have drift issues, and then there’s a bunch of other technologies like ultrasonic, magnetic resonance, whatever technology you choose will require some kind of sensing infrastructure to be installed,” Davies said. The result? “There are issues with scalability and cost.”

He says that SLAM and machine vision algorithms, which are growing toward maturity themselves, may present the way forward. According to the points Davies laid out, it’s clear that AR isn’t ready just yet, but we’re pushing hard to get it there.