The Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada’s Annual Meeting (PDAC) came to Toronto at the beginning of March. With projected visitor numbers in excess of 27,000 this is one of the biggest—if not the biggest—mining industry events in the world. In the exhibition halls you will find everyone from junior mining firms in the Investor’s Exchange marketing new projects through to companies selling a plethora of services, equipment or software targeted at mine exploration, and operation activities.

I spent the event working the Sumac Geomatics stand promoting our remote sensing services; especially UAV-based magnetic surveys to service the exploration industry. UAVs are now commonplace across the mining industry, established in operations such as volumetric measurements of open pits or tailings piles. Perhaps as a result of the extent of Canadian innovation in the mining industry, this year there were at least just as many underground UAV applications being marketed as above-ground applications.

Underground mining 101 – What is a stope?

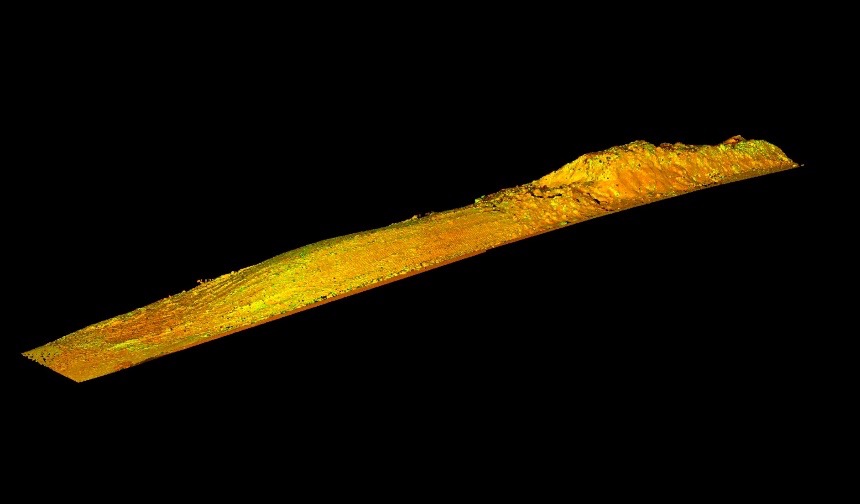

The objective of any mining operation is to extract the maximum volume of valuable ore from the earth at the lowest production cost. Mines invest in geophysical surveys to assess the most likely spatial extent of the target ore body, and then design an infrastructure of access shafts and drifts to most efficiently access and extract the ore. To release the ore, blasting operations need to be designed that excavate the ore, resulting in a stepped formation known as the stope.

The operation needs to strike a balance. On one hand, they do not want to over blast and increase the volume of waste material mixed with the ore, material that needs to be transported out of the mine (overbreak) and leads to increased stope dilution. On the other hand, they do not want to under blast and leave valuable ore in the mine (underbreak). The extent of overbreak and underbreak is assessed by monitoring the volume of the excavated stope and comparing to the formation of the ore as measured in prospecting activities.

The stope is a highly dangerous environment to work in, as it is still an active environment after the blasting and rocks loosened from the blast are still likely to fall. Traditional survey methods require mining personnel to stand on the very edge of the drift overlooking the stope. There is a limit to the number of survey points that can be collected using traditional methods.

The Cavity Monitoring System (CMS)

The result of a joint venture between Canadian firms Noranda Technology Centre (NTC) and Optech (now Teledyne Optech) in the early 1990s, the tried-and-tested technology used for stope surveying is the CMS system. While it has gone through a series of iterations over the years, a CMS system consists of a rotating laser range finder mounted on an extendable boom that the mine surveyor can insert into the stope while standing much further back in the drift. Updated versions of the CMS include carts that help to better insert the system into draw points, sensor updates that permit higher resolution point clouds to be collected in conjunction with simultaneous video imagery, and wireless operation capabilities that place the mine surveyor even further back from harm’s way.

A schematic view of CMS operations

Technological advances aside, over almost 30 years the CMS has become integrated with the standard CAD and mine planning software and workflows used by the mines. As a former CMS salesman, I can also tell you that I have witnessed the abuse in the stope that these robust systems take, but it is of course better that the survey systems take the impact of falling debris rather than the mining personnel themselves.

UAVs and increased autonomy

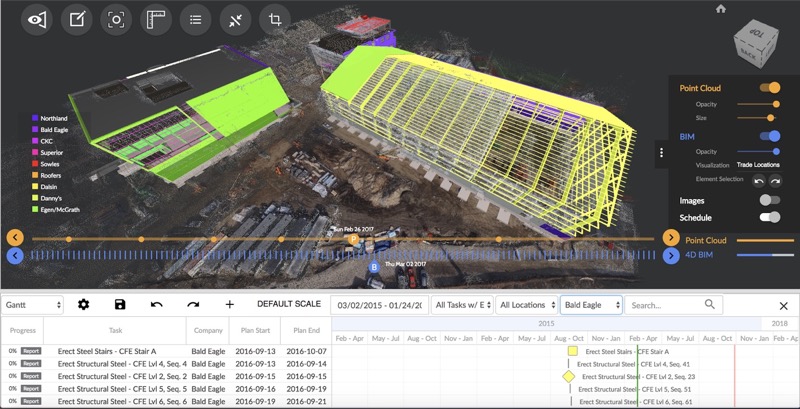

In the same way that advances in robotics and sense-and-avoid workflows are bringing autonomous road vehicles and unmanned aerial operations to the fore, these advances are bringing increased autonomy to underground monitoring operations too.

Furthermore, since in the underground mine it is the mine company that has jurisdiction over flight rules, the advances are having a greater effect. New simultaneous location and mapping (SLAM) techniques mean that UAVs are already flying autonomously in GPS-denied environments, collecting high resolution 3D data.

UAV mounted Hovermap payload in a mine

Systems such as Emesent’s Hovermap (reported on SPAR3D in 2017) are now seen globally, but at PDAC we also saw underground UAS systems by Canadian firms such as the Robotics Centre’s Prospector, Clickmox’s Minefly and now Safesite Exploration’s system too.

These tools implement variations of similar SLAM and autonomous algorithms; in my opinion these systems make far better use of lidar sensor types such as the ‘puck’ than strict survey applications. In this application, the lidar data performs the dual function of providing input to the SLAM algorithms and collecting point cloud data at resolution can higher than from regular CMS operations.

The team from North Bay Ontario’s Safesight Exploration Inc. at PDAC

Being small enough to be carried into a mine by a single person, the autonomous flight algorithms have the potential to set the operator even further back from danger than the conventional CMS boom method. These systems have the potential to bring efficient mapping to more than stopes, as they can be used with associated drifts, shafts and access roads, as well as for collecting data for rock walls at resolution high enough to be used to monitor cracks and distress in the rock face.

Surely UAS approaches are more efficient?

The autonomous nature of UAS systems and higher resolution of data that they collect, does indeed bring a credible new tool and approach to production monitoring and planning. To assess the extent that they replace existing methods though, we need to consider the over environment and operational context that they are used.

Questions remain about operational safety, dependability

Mines are dangerous and highly regulated environments. Even as an autonomous UAS keeps mine personnel out from the stope, and even further way from the highest risks than traditional CMS-based approaches, the fact that they are operating underground does not bring a complete ‘free-for-all’ in their use.

In UAS marketing materials we see little written about what other operations need to cease in a drift while the UAS is in operation. With UAS systems often considered “disposable,” there is an assumption that it is not a problem to lose equipment due to propellers encountering a rock face as a result of variations in the tolerance of navigation algorithms. But the questions remain: What is the general guidance for how far operating personnel need to be away from UAS systems in case there is a crash? What types of traffic control protocols are required for operating multiple or swarms of systems underground? What type of interference could a magnetic ore body bring to the safe operation of these systems?

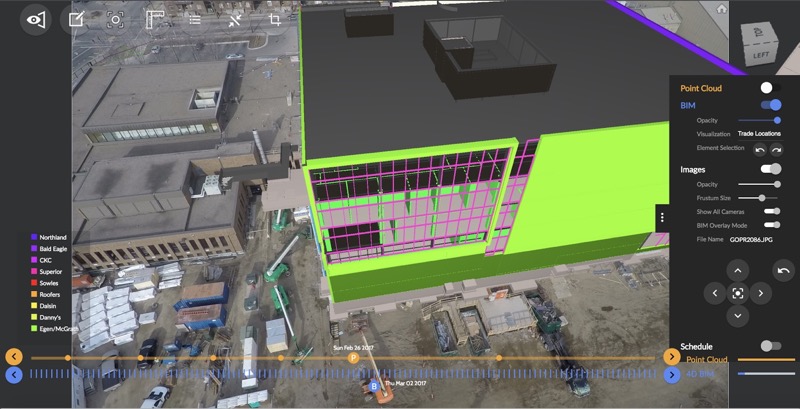

Clickmox’s view of UAS stope survey versus CMS stope survey

At least one of the vendors at PDAC explain how their system can be operated by a non-surveyor UAS professional, whereas other vendors discuss the value of bringing the expertise of the specialist service provider to site. What impact does in-house operation of these systems have on the dependability of data collected for production monitoring and safe operation?

Perhaps the underground UAS service operators are already bring best-practice to the table regarding the above, but thought there has been considerable discussion in the above-ground UAS industry on flight regulations, I have yet to see similar discussion on underground protocols.

Usability of data

The sensors in the underground survey system payloads do indeed provide the opportunity to collect data that may not have been possible otherwise, especially within linear drifts and for remote hazard analysis of rock faces. However, data at this higher resolution still requires knowledge of point cloud manipulation to spatially align and position the point clouds that are collected. Various CAD and mine planning software also have differing capabilities with regards to the extent to which these point clouds can be processed. This means these systems are often operated by specialist 3rd party service providers.

On the other hand, CMS data has been considered fit for purpose for many years. The routines for managing and processing it are well understood and production personnel understand how it relates to production planning procedures. It is unusual for a CMS specialist service provider to be required, as the entire CMS stope survey can be performed by onsite mining personnel.

Technology innovation brings options

The recent advances in underground UAS technology and operations means that mine operators can collect data and intelligence on their mine that might not have been possible previously. Increased autonomy brings increased options to survey mines with a higher degree of safety, but any operations need to be undertaken in the context of all other mining operations.

For specifically undertaking stope surveys to measure stope dilution, currently CMS operations still have their place. These are known systems that are fit for purpose, and that the mines understand. Yes, in some mines, UAS operations will replace the CMS and be used to measure other aspects of the underground mining infrastructure. While there can be a push to use the newest technology, in my opinion the industry needs to consider how best to implement the UAS both from a safety/operations context, and in terms of the back-office management of its data – which will be considerable. While UAS do now bring benefits to the mine operator, it is for these reasons why I believe we will see UAS and CMS approaches being used for some time to come.