Article contributed by Norman Mucha, Esri

Few US cities are as steeped in historical memory as Washington, DC. Yet, DC’s population is increasing faster now than at any time since the 1950s. Data from the 2020 US Census revealed that it is the country’s seventh fastest growing city, burgeoning at a rate twice the national average. To keep the city livable for all, the District is looking at how to preserve its heritage while guiding growth and change.

Navigating this tension is a key goal of the DC Office of Planning. Guided by modern tools, including a digital twin powered by geographic information system (GIS) technology, the agency is striking a balance between preservation and growth. Planners map and model proposed changes while keeping the communities informed.

Development is not evenly distributed within the city. The adjoining Cleveland Park and Woodley Park neighborhoods are growing at one-third the rate of the city overall. Their current restrictive zoning and added layer of preservation requirements hamper development.

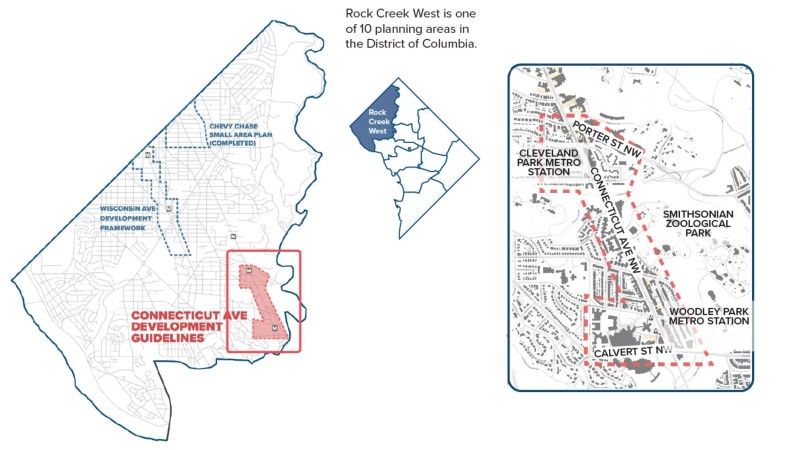

The two neighborhoods are part of a region of DC that city planners call Rock Creek West planning area. It covers over ten percent of the city—everything west of Rock Creek Park and the National Zoo—but contains just one percent of the city’s dedicated affordable housing units.

This imbalance resonates across the city. “Because Rock Creek West has not really contributed to increased development and growth in the District over the last few decades, it puts pressure on other neighborhoods to absorb this demand, causing more areas to become less attainable,” said Heba ElGawish, a planner with the DC Office of Planning.

To create a more equitable DC, the District set a goal of adding 36,000 new housing units, including 12,000 affordable units by 2025, with specific targets for each of the District’s 10 planning areas. The Office of Planning worked to embed these goals in the District’s Comprehensive Plan by adopting new land use designations near transit stations and along major corridors, including Connecticut Avenue corridor that crosses Cleveland Park and Woodley Park.

Managing Growth in Historic Districts

Cleveland Park and Woodley Park were once rural, dotted with large estates. A remnant of Rosedale, the largest, is the oldest home in DC. Cleveland Park derives its name from an estate owned by President Grover Cleveland.

In the late 19th Century, the opening of the Rock Creek Railway along Connecticut Avenue connected the region with the rest of DC. These trains ushered in the steady urbanization of the area culminating with the arrival of the subway in 1981. New stations along Connecticut Avenue brought DC Metro trains to Cleveland Park and Woodley Park.

The arrival of Metro catalyzed efforts among local residents to protect the area from further development. In 1987, the city’s Historic Preservation Review Board certified Cleveland Park a historic district. Woodley Park followed three years later.

“The two commercial areas were downzoned as a result,” ElGawish said. “The neighborhoods got locked into the built environment they already had.”

Now, the District of Columbia’s Comprehensive Plan argues that Metro stops, including Cleveland Park and Woodley Park, are optimal sites for transit-oriented development.

“Given this proximity to high-capacity transit as well as parks and civic amenities, they are ideal for accommodating more housing and more jobs,” ElGawish said.

Smart City Planning

ElGawish and her colleagues examined high-capacity transit corridors like Connecticut Avenue and amended future land use to allow for denser development. Some sections previously designated only for low-density commercial buildings now also allow for medium-to-high-density residential development.

For ElGawish and others in the DC Office of Planning, their location-enabled digital twin helps them understand challenges, craft solutions, and communicate ideas to the community. Using the smart city planning software, ArcGIS Urban, they can simulate how proposed changes would alter a neighborhood’s character.

“It’s an opportunity to visualize different land use and development scenarios, especially in historic districts, where design is a major component of what we’re trying to achieve,” ElGawish said. “It can be helpful to generate development scenarios, look at the breakdown of market rate and affordable housing, and test how different massing and height configurations impact those numbers.”

Cleveland Park and Woodley Park have strict caps on the number of restaurants allowed. GIS lets planners visualize and analyze how relaxing these requirements would affect these stretches of Connecticut Avenue.

The team also uses GIS to design changes that draw attention to overlooked areas. ElGawish noted that although the National Zoo abuts the commercial districts on Connecticut Avenue, the businesses there receive very little foot traffic from zoogoers. She and her colleagues use GIS to consider signage placement and streetscape changes that increase awareness of these areas.

Working with GIS is also a way to link numeric data with reality.

“We normally do development configurations and put the numbers into spreadsheets,” ElGawish said. “So I’ve been exploring how that could be streamlined with GIS if we can quickly generate [models of] these configurations.”

Assuaging Community Concerns

Communities that have advocated for zoning restrictions are wary of major changes. ElGawish and her colleagues use the digital twin to address their concerns.

During the early stages of the Connecticut Avenue project, the Office of Planning organized a public walk around the area. Planners described the coming changes and answered questions. The office followed up with a virtual walking tour using ArcGIS StoryMaps.

“We’re nearing the end of the planning process for Connecticut Avenue,” ElGawish said. “The Connecticut Avenue Development Guidelines have been adopted by the Historic Preservation Review Board, and we’re aiming to make ArcGIS Urban part of our place-based planning workflow.”

Learn more about how planners use GIS to plan and design inclusive and vibrant communities.

This article originally appeared on Esri Blog.

Norman Mucha is an account executive on the Esri Smart Cities team, working to ensure customers have the best combination of products and services, particularly with regard to their planning needs.

Norman Mucha is an account executive on the Esri Smart Cities team, working to ensure customers have the best combination of products and services, particularly with regard to their planning needs.