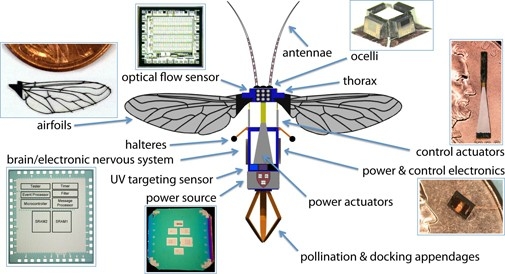

The University of Buffalo is teaching robotic insects to see with LiDAR. This effort is part of the “RoboBee Initiative” (I couldn’t make this up), which includes researchers from Harvard and the University of Florida working to develop biologically inspired robots for use in applications like agriculture and disaster relief.

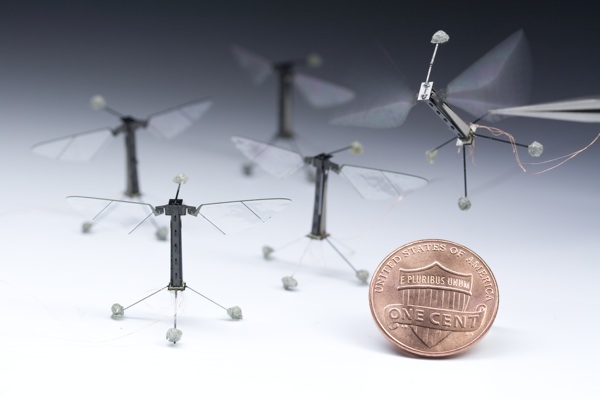

The best way to teach these miniature robots to see is to equip them with LiDAR sensors like those used for self-driving automobiles. “Only we need to shrink that technology so it works on robot bees that are no bigger than a penny,” explains University of Buffalo computer scientist Karthik Dantu.

The challenge is big but pressing, as LiDAR technology is necessary for these drones to do their jobs properly. As UB explains, researchers have shown that these RoboBees are capable of flight when tethered and can move while submerged in water. The problem is that they have no depth perception, which means that they would be impossible to control.

University of Buffalo says that the University of Florida will develop the “micro-LiDAR” sensors, while Dantu works on the data processing algorithms that allow the bee to navigate its environment.

As Dantu describes it, equipping these tiny drones with LiDAR eyes means they would be able to perform precise tasks—even landing in a flower. In the next five years, the team hopes to use a $10-million grant from the National Science Foundation to build a swarm of autonomous bees programmed to perform precise tasks in coordination with one another.

Possible uses for these swarms of mini drones include hazardous environment exploration, military surveillance, high resolution weather and climate mapping, and traffic monitoring.

Artificial crop pollination seems like an obvious use for these drones, but the team explains that they don’t see that application as “a wise or viable long-term solution.” In other words, we can’t just replace nature’s drones with robotic drones and hope for the best.

As you may have guessed, a LiDAR unit smaller than a penny will not be limited to use in tiny bees. “The sensors could be used,” University of Buffalo describes, “in wearable technology; endoscopic tools; and smartphones, tablets, and other mobile devices.”