ILMF (part of Geo Week) kicked off in Denver last week with a focus on the use case for 3D technologies—or, more specifically, the data. The keynotes were presented from perspectives outside of the mapping industry, but illustrated important movement in 3D technology at large that may be fruitfully applied within the mapping industry.

A problem: the imminent data explosion

Peter Batty delivered a keynote about how consumer-level reality capture technologies are changing the way we capture data for GIS applications. Batty began by reviewing the speedy evolution of the smartphone’s depth-sensing capabilities, the falling price of 360-degree cameras, and the increasing sophistication and miniaturization of drones. He argued that we are seeing rapid increases in the volume of data being collected by many different types of reality capture devices.

He also pressed professional communities to consider the implications of this growing volume of data as it pertains to data-handling and dissemination requirements, as well as how we can use it to respond to the need for increasingly intelligent data deliverables.

Peter Batty highlights the imminent explosion of data volumes and availability

The keynote presentation by Barry Behnken from AEye focused on the high volumes of data produced by autonomous vehicle sensing.

Behnken raised a point that complements Batty’s, arguing around 80% of the data collected by the lidar systems on autonomous vehicles is essentially thrown away. This is because traditional data processing procedures fall prey to latency problems that make them inadequate for dealing with the sheer volume of data they receive from autonomous vehicles. As a result, much of the information collected becomes obsolete before it is even processed.

Latency arises when processing voluminous data from autonomous vehicles

A solution: artificial intelligence in practice

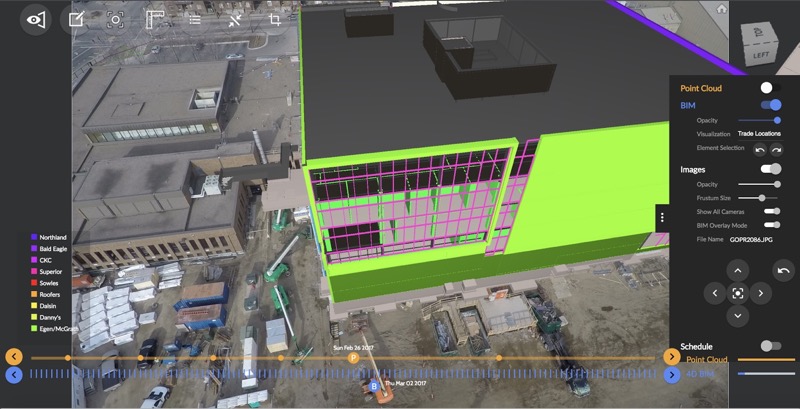

Batty described how GIS-related industries have responded to this problem. It is becoming commonplace, he argues, to automatically process reality capture data using sophisticated image-, edge-, and text-processing algorithms. For example, Google now generates most of the attribute data for Google Maps automatically. Batty’s own firm IQGEO has been exploring the use of Mapillary, which uses computer vision to compile comprehensive geospatial maps from crowdsourced imagery, to improve the functionality of its MyWorld application for the utility sector.

Implementing increasingly artificially intelligent routines to classify 360-degree imagery for utility companies

During his discussion of the data synthesis requirements of autonomous systems collecting huge amounts of data, Behnken argued that we sometimes put too high a value on increasingly dense point clouds. He explained that an autonomous vehicle needs a synthesized set of information in real-time—not just a ton of raw data—to make critical sense-and-avoid related decisions when planning its path. This will likely require artificial intelligence.

What does an autonomous driving system really need?

Requirements for autonomy and validation

Geoweek’s keynotes were presented from perspectives that may have been abstract to traditional mapping communities, but have brought front and center the fact that other industries are already implementing artificially intelligent techniques for disseminating data from reality capture systems.

Still, the requirements of these industries are different from those of the mapping industry. In the utility space, there is a similar requirement to record what has just been built, or to assess many environments along a distribution network for access purposes. However, the purpose here is ultimately to assess whether there may be an issue as opposed to exactly what that issue is. The utility industry, in other words, does not require information products to be as precise as we do in mapping.

For autonomous vehicles, the requirement is not precision, but speed. Vehicles need real-time processing to assess the possibility that an object in a scene might cause a collision, which it can do even if the positioning of that object is not exact.

For many mapping applications the requirement for precision is much higher. As we embrace autonomous techniques for processing our data, and even borrow these techniques from the utility space or autonomous vehicle space, we need to think about what the use-case requires of the data that we are processing. This is true now more than ever.