It’s a question as old as the 3D data-capture industry, itself: Just how is the demand for data capture linked with the growth of 3D printing? (Here’s me noodling on it almost a decade ago, in fact.)

On the one hand, it sometimes seems like not at all. Most 3D printing is done from digital files that were never physical objects in the first place. And most laser scanning and photogrammetry is focused on large things or places that will likely never result in models that will be 3D printed.

But every few months or so, a scanning-printing collaboration comes along that makes you wonder. I remember the MakerBot store on Boston’s Newbury Street, where I took the kids a time or two. It was pretty cool!

Fun takeaways from the store include $5 gifts from their “gumball machine,” such as mini Faneuil Hall and Fenway Park novelty items, and visitors can also use a 3D photo booth, which takes just one minute to scan the subject’s head and shoulders, shipping the end-result to your doorstep.

But, after opening in 2014, it ended up closing in 2015. Not enough demand for 3D printed heads (or 3D printers in general) to justify a Newbury Street address, apparently. Which makes sense. Why try it out on the highest-end shopping street in New England? Wouldn’t it have been a better fit at the North Shore Mall or something?

Regardless, MakerBot is still going strong – my kid plays with one at school all the time. But he most definitely does not play with a 3D data capture device of any kind. They just build things in various 3D design programs and then print them out. Why isn’t there a version of the Artec Space Spider that’s $2,400 instead of $24,000, so that the tech is available to schools and gets kids’ minds working on 3D capture problems and solutions? Or a HandyScan that’s $3,500 instead of $35,000? Is it just not possible to create cheaper tech, skimp on the precision a little bit, and still get useable scans?

Not just any $4,000 bike. A 3D-printed $4,000 bike.

With the rapid increase in technological capability that 3D printers are experiencing, it’s vital that data capture firms lay the groundwork now for the scan-to-print pipeline. Because all of the money streaming into printing is only going to speed up that technological advancement.

Most recently, Arevo, makers of the 3D-printed bike, landed $25 million in seed money and retained big-name CEO Sonny Vu, who’s already built and sold a company to Apple for $260 million. They’re making big stuff, as a niche printing operation, where they’re not selling machines, they’re selling parts. Which makes sense, considering the $1m price tag for each machine.

Is there a business model in scanning parts for print and delivery, essentially white-labeling Arevo’s 3D printing service?

Or, when you consider the precision that’s likely needed for success, is there a business model in high-precision testing and validation of 3D printed products for companies like Relativity, which recently raised $140 million to build rockets for space?

Or what about the promise of Desktop Metal, which is close to half a billion dollars in fundraising and is backed by the likes of Ford, BMW, and Lowe’s? Given the money in vintage cars alone, is there a business in scanning old gaskets and pistons and having them printed and delivered?

Clearly, there are plenty of hurdles, as I’m not the first to ask these questions. Maybe the lack of any big successes here says the numbers just don’t work, but there are clearly some people giving it a go. Tyr3D seems to have been an early entry to the business, but their web site doesn’t load anymore. Javelin Tech has a nice case study of making the custom car parts happen from scan to print, using an Artec, Geomagic, and Stratsys combo-package of a solution. HV3D has gotten some good press and seems to have a network of garages they’re working with.

But Jay Leno was doing that in 2009. Has innovation stalled? What’s the killer app?

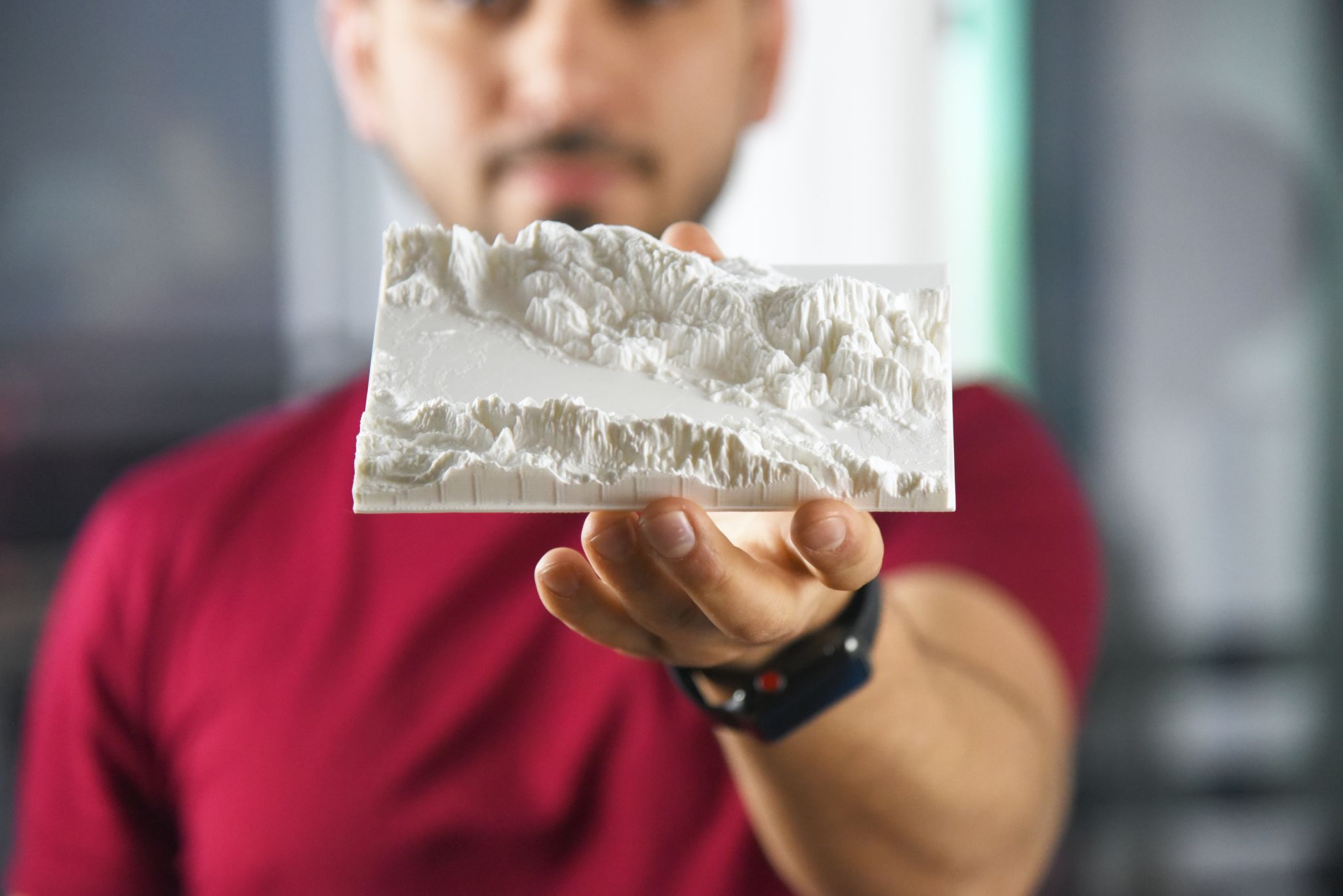

In case you want to scan and print a copy of your clay dinosaur.

I did notice that Fictiv bought some google ads for “scan-to-print” and some other variations. Maybe they’re trying to gin up a little more business there?

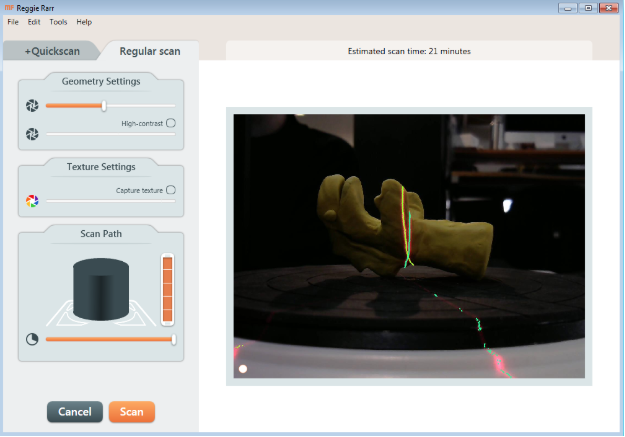

And this post on Matter and Form offers a great little workflow, but is still very much for the hobbyist and tinkerer. It’s not an industrial or business-focused solution.

Maybe the two industries will never be much linked beyond the very niche application, but when you consider the money flowing into printing, as contrasted with the money flowing into data capture, it seems like it behoove the data capture industry to get creative and try to ride those coattails a little more ardently.