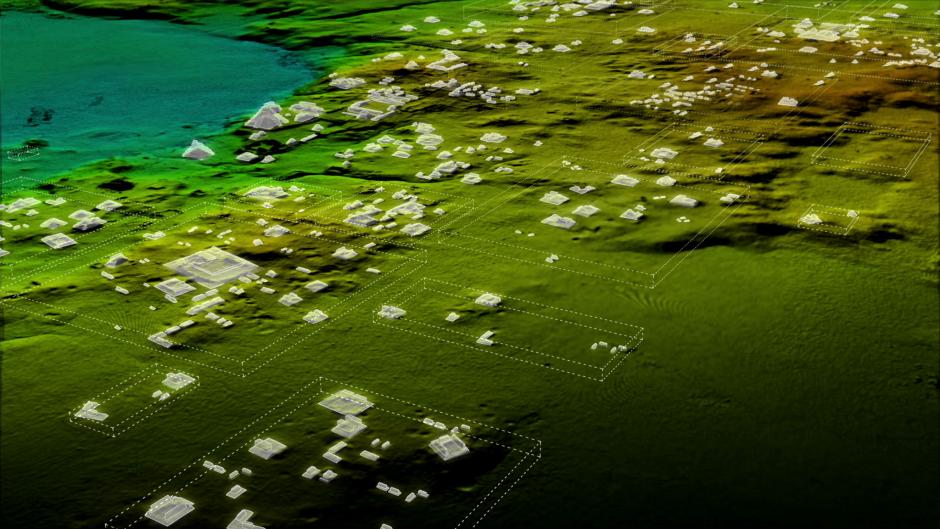

In February of 2018, the mainstream press was abuzz with the news that a group of researchers had lidar-scanned large swaths of the Maya reserve in Guatemala, and made a number of huge discoveries while poring over the data. Funded by the Guatemalan nonprofit the PACUNAM Foundation, the researchers were able to strip the trees out of the point clouds and find upwards of 60,000 new structures, as well as a large number of agricultural systems, earthwork ditches, and rampart systems. The settlement turned out to be a great deal more complex than anyone imagined.

One of those researchers is Ithaca College archaeologist Thomas Garrison, a keynote presenter at the International LiDAR Mapping Forum this month in Denver, CO. (Register here!) I caught up with him ahead of the conference to discuss the ways lidar is changing the age-old discipline of archaeology, why researchers need lower-priced systems as quickly as vendors can make them, and a few other details about the project you might not have picked up in the press coverage.

SPAR 3D: Given the scale of this discovery, it seems like the coming of lidar to archeology represents a huge historical turning point.

Garrison: I’d say yes and no. One of the big misconceptions we’re noticing is that people see the images and they say, “Why don’t you go check out that site?” Well, because we only digitally took off the forest—we still have to get there.

For us doing the field work, it’s a blessing to have the data because we’re not just setting out and hoping we’re going to find something that day. When I started out in this back in the early 2000’s using multi-spectral satellite imagery, some days we’d get to a place where we saw a little discoloration in the vegetation, and there would be ruins there. Some days we’d walk and we wouldn’t find anything. Now, you’re going to reach what you’re looking for, but the journey to get there has not gotten any easier. You know, I wouldn’t want it any other way. For many of us that get into the field of archeology, the most exciting part of it is doing the field work.

So technology can only do so much, and there’s no replacing the actual field work. That seems like a sentiment a lot of lidar users can relate to. However, it seems like the specific technology you’re using makes a huge difference in archaeology.

I think one of the things that stood out to us is that the actual sensor you’re using matters. You know, this is stuff that has been worked out by the National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping, who’s done a number of flights with different sensors over different parts of the Maya area. The original studies were done with this Teledyne Optech Gemini and ours is with the Teledyne Optech Titan. The Titan just had a so much more powerful laser, and it’s collecting that much more data, and it’s letting us see more subtle features. The lasers are getting in at different angles, which is getting us better returns. Those are things that people that aren’t as familiar with the actual sensor side of things aren’t necessarily realizing, like those in my field.

Do you have any future wants or needs from lidar technology?

The thing that’s always going to cause problems is the cost, right? And it’s not just the cost of the sensor. You know, the archeologists aren’t the people that are out there flying the plane, collecting the data, getting it off the instrument, calibrating it, and running the algorithms, so that costs archaeologists lots of money.

In my field, we’re in this awkward phase where a lot of us now do have access to lidar, but there’s still more than 90 percent of the Maya area that hasn’t been covered with this stuff. What we’re finding is that every single place where we get lidar, it’s just a totally different world than anything we thought before. So now it creates this research problem where if you don’t have lidar, what can you really say about the settlement in your area? But it’s not reasonable to expect everyone to get lidar. Because of the cost.

Courtesy Wild Blue Media/National Geographic

When I was reading about this project, it sounded as if the arrival of lidar in archaeology was a clear victory. Would you still say it’s a revolution?

We are certainly in a geospatial lidar revolution right now. But the PACUNAM lidar initiative for the project I was involved in got 2,100 square kilometers, maybe a little bit more. The Maya Biosphere Reserve, which is the protected area in northern Guatemala, is 21,000 square kilometers. So our project captured only 10 percent of the area in Guatemala—and the Maya are also throughout the Yucatan Peninsula, in places like Belize, Honduras. So there’s just a ton of more areas where we could collect these data.

And then the other part of that revolution is getting a new generation excited about the Maya. After 2012 passed when there were all these Maya apocalypse things out there, people went on to the next big thing. This is sort of drawing attention back to understanding Maya archeology and we need people that sort of have that sort of adventuresome field work type mindset, but also have the technical chops to be able to sit in front of the computer and process the data and identify features and get ready for the next round of field work.

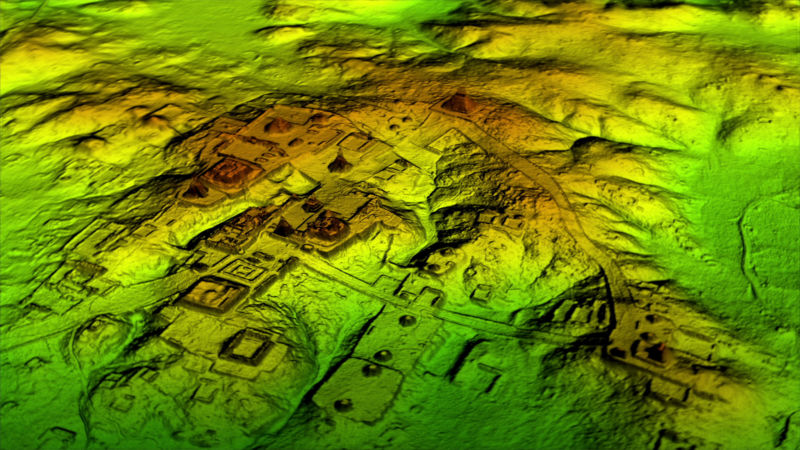

A buried temple in the Maya Biosphere Reserve. Under a creative commons license.

Do you have any other unexpected findings as a result of the lidar data that you might want to talk about?

The major findings of our broader project that we published in Science were these large regional trends. The big one that came out in the news a lot was just the sheer density of the settlement—60,000 new structures within this area. Whatever that translates into an ancient population, that’s something that’s actually really difficult to calculate. I can tell you that we’re talking about three to four times as many structures out there as we than we previously thought. But then agricultural systems are appearing and these are things that we knew existed, because we found little traces of them occasionally, but lidar sort of lays them bare.

The big thing for me specifically are these large defensive features, these earthwork ditch and rampart systems that we’re finding in different areas. I’m working in this heavily defended landscape and we actually discovered what can only be described as a full-blown fortress using the lidar data. And it’s not really something that we’ve seen before, something built just for that purpose. I think this is the first case where we’re taking a site that was totally unknown before Lidar and are now moving forward with an excavation of it based on preliminary findings.

Before we let you go for the day, could you give me a sense for the thrust and shape of your presentation?

The idea is to show how transformative lidar can be in a field that people don’t maybe think about in terms of high tech. That’s been the great thing that lends itself so well to the press—you’re using this cutting-edge technology to study this really ancient old stuff. It’s just a total disconnect. And yet, it’s something where a technology has turned the understanding of an entire field on its head, after over a hundred years of research. It’s just cool to know that those sorts of things can still happen. There are not that many total revolutions in the sciences anymore. A better turning things their head and in this case, it is totally driven by lidar.

Interested in hearing more about Dr. Garrison’s use of lidar to uncover the secrets of the ancient Maya? Attend the International LiDAR Mapping Forum (ILMF) where he’ll be presenting during the opening keynote session on Monday, January 28. Register here.