‘Our sweet spot is construction support’

BOSTON—While the Big Dig, a decades-long tunneling and transportation project here, may have come to be synonymous with boondoggle in some observers’ opinions, it can at least be credited for raising the profile of laser scanning in Boston.

“We didn’t invent them,” jokes Michael Clifford of 3D laser scanners, which his firm, DGT Survey Group, part of Digital Geographic Technologies, has been using since the early 2000s. “We starting using the laser scanner on the Big Dig,” he says, “which was the first big push for scanning in Boston. We were contracted on the Big Dig for several years. We sort of grew out of the Big Dig.

At this point, the company has three scanners, a FARO Photon being its lead instrument, with four of its 14 surveyors trained to use the scanners at varying levels. The company is growing, too. This month, DGT added a North Shore office, which opens up possibilities for expansion of services into New Hampshire and Maine as well. The office comes as Oak Engineers closes its doors and Oak’s Edward Dixon and Taylor Turbide come to DGT. Clifford says intitially there won’t be a lot of laser scanning done from the new office, as the carryover clients there are largely light commercial and residential and not necessarily fits for the scanner’s capabiltities.

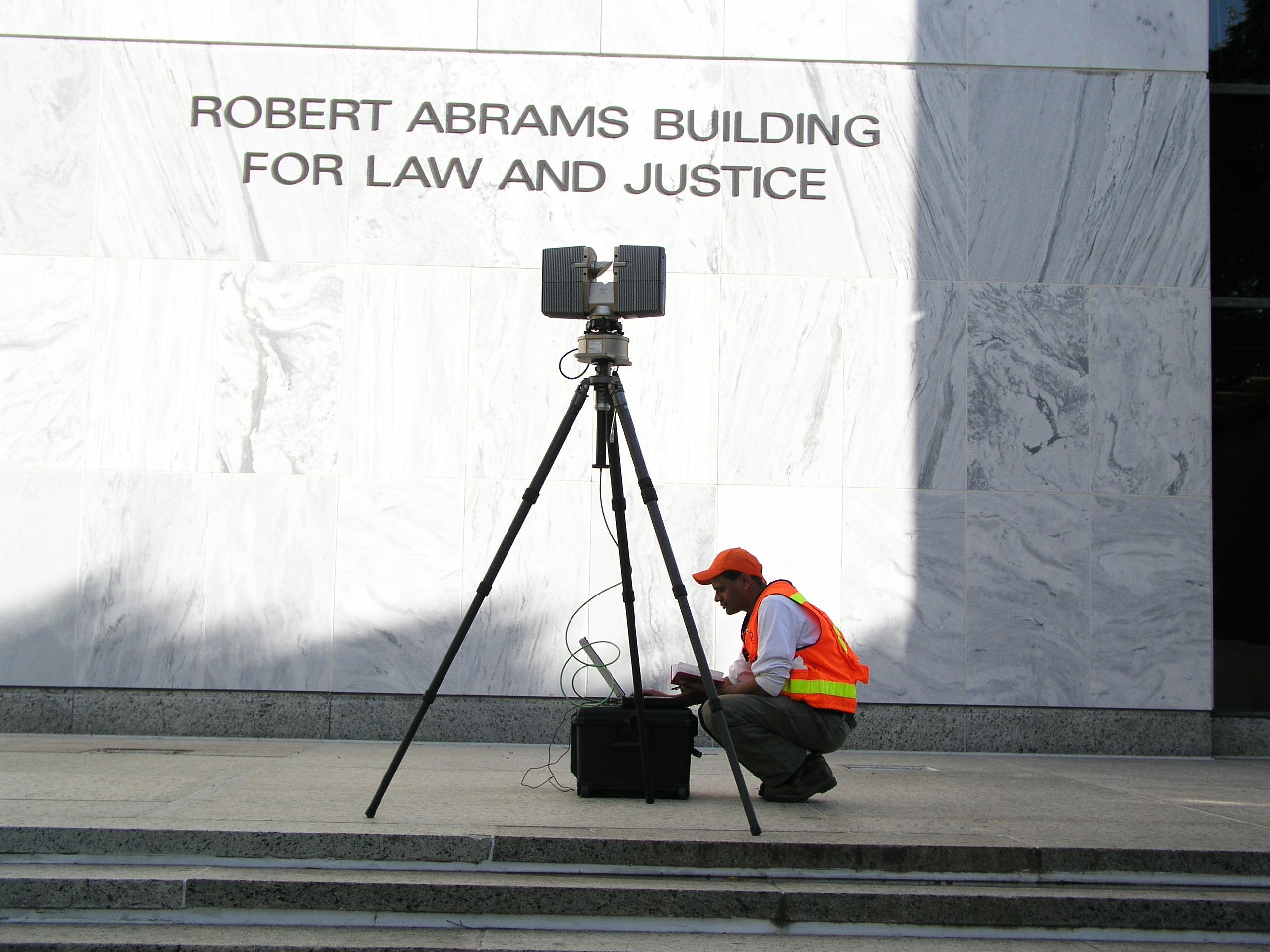

But Cliffords says the scanners aren’t just for the big and intricate jobs. “We use it for the clients we already have,” he says. “Our sweet spot is construction support. We scan to establish existing conditions, and sometimes for forensics in construction, making sure things were built the right way.”

But there are a number of other applications as well, from scanning building facades as part of historic restoration projects to scanning the interiors of buildings that are being put out to let (even condominiums) to establish precisely the square footage.

“Fit outs are a growing thing,” Clifford says of the real estate market and its potential. “If an existing office space is being fit out, surveyors are sometimes brought in, if it’s high-end enough, to measure up the space.” Using the scanner can make the work quicker, depending on obstructions and the shape of the space.

Sometimes, though, DGT might bring the scanner in even if it isn’t absolutely necessary, as the scanner itself is a valuable marketing tool.

“People call us because they think of us as the high-tech guys,” he says “It’s a differentiator. There are a lot of surveyors out there, and not a lot using scanners. It does separate us.”

“We’ve been called into projects specifically because we have the laser scanner,” Clifford says. “I’ve been in situations where I’ve had to actually talk people out of using the scanner. People think it’s magic.”

However, there’s no denying “it’s kind of a fancy expensive calling card,” Cliffords says. “It shows that we’ve made an investment in the best technology, and some sophisticated clients do respect that.”

Currently, DGT is doing all of their processing in house, though the company has considered some outsourcing. “That’s coming up a little bit with BIM,” Clifford says. “With our construction clients, BIM is the hot thing.”

The problem, Clifford says, is that laser scanning doesn’t integrate directly into Revit, and architects haven’t yet latched onto laser scanning en masse. “The construction managers really grasp what the scanner can do for them, but the architects can’t seem to work it into their workflow,” he says.

“The next big leap is for end users to work right in the point cloud, which will cut out the modeling work, which they don’t want to pay us for anyway.”

Even for new-build work, Clifford says laser scanning can be valuable, especially in an urban setting. “If you’re going up in a tight urban area, the existing plans of the immediate area only show you what’s on the ground,” Clifford says. “It doesn’t show the chimney flues, the fire escapes, all the obstacles that on the outsides of buildings. Scanning is the only way to get those measurements.”