For those who joined us in person at the SPAR 3D Expo & Conference in 2019, you may remember the keynote from MiMi Aung of the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. In her presentation she outlined the key challenges to a very unique problem: designing a drone meant to fly on another planet.

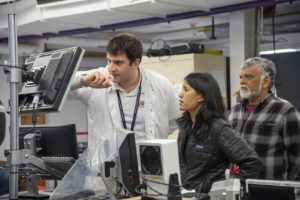

Teddy Tzanetos, MiMi Aung and Bob Balaram of NASA’s Mars Helicopter project observe a flight test at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“The Martian atmosphere is only about one percent the density of Earth’s,” said Aung.

“Our test flights could have similar atmospheric density here on Earth – if you put your airfield 100,000 feet (30,480 meters) up. So you can’t go somewhere and find that. You have to make it.”

The project has come a long way since we got an overview in Anaheim.

The “Mars Helicopter”, now named “Ingenuity” is tucked in a payload underneath Perseverance, the latest NASA Mars Rover. On February 18th, the rover made a safe landing (and survived the “seven minutes of terror.”)

After a few days of testing and calibration, part of the mission to Mars will include a series of short flights where Ingenuity will fly, navigate and land safely again – without human intervention.

Realistically, these flights will be more proof of concept than anything else – but will demonstrate that flights like this are possible – which could pave the way for other 3D surveying, lidar terrain mapping, or other reconnaissance missions going forward.

Delays are an inherent part of communicating with spacecraft across interplanetary distances, which means the helicopter’s flight controllers at JPL won’t be able to control the helicopter with a joystick or to look at engineering data or images from each flight until well after the flight takes place.

Therefore, Ingenuity will make some of its own decisions, based on parameters set by its engineers on Earth. Ingenuity has a kind of programmable thermostat, for instance, that will keep it warm on Mars. During flight, Ingenuity will analyze sensor data and images of the terrain to ensure it stays on the flight path programmed by project engineers.

In an interview on IEEE Spectrum, Tim Canham (Mars Helicopter Operations Lead at NASA JPL) describes the aim of these flights.

“Because we’re trying this out for the first time, we have three main flights planned, and all three of them have the helicopter landing in the same spot that it took off from, because we know we’ll have a surveyed safe area. We have a limited 30 day window, and if we have the time, then we might try to land it in a different area that looks safe from a distance. But the first three canonical flights are all going to be takeoff, fly, and then come back and land in the same spot.”

Its navigation is as slim on processing as possible, and will also be a proof of concept for utilizing sensors and images for navigation on other worlds, says Canham.

“We use a cellphone-grade IMU, a laser altimeter, and a downward-pointing VGA camera for monocular feature tracking. A few dozen features are compared frame to frame to track relative position to figure out direction and speed, which is how the helicopter navigates. It’s all done by estimates of position, as opposed to memorizing features or creating a map.”

Ingenuity has now survived the dynamic environment around launch and proved it can charge its off-the-shelf batteries in space. Flying over the surface of Mars will confirm results from flight tests performed in special space simulation chambers and provide insights into operating a helicopter on Mars.

Ingenuity is intended to demonstrate technologies needed for flying in the Martian atmosphere. If successful, these technologies could enable other advanced robotic flying vehicles that might be part of future robotic and human missions to Mars. Possible uses of a future helicopter on Mars include offering a unique viewpoint not provided by current orbiters high overhead, or by rovers and landers on the ground; high-definition images and reconnaissance for robots or humans; and access to terrain that is difficult for rovers to reach. A future helicopter could even help carry light but vital payloads from one site to another.

Learn more about the Ingenuity mission here: https://mars.nasa.gov/technology/helicopter/