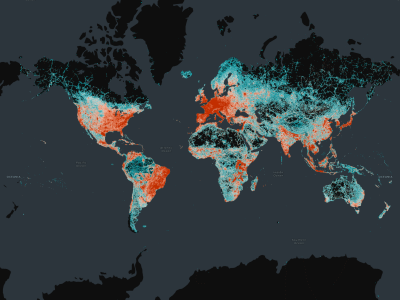

Late last month, the Overture Maps Foundation announced the release of their first world-wide public release of their open map data. The initial dataset, Overture 2023-07-26-alpha.0, includes four data layers: Places of Interest, Buildings, Transportation Network, and Administrative Boundaries, the specifics of which you can learn about here. These were derived using open and contributed map data through a variety of channels, and released in the Overture Maps data schema, introduced in June of this year.

The formation of the Overture Maps Foundation (OMF) was facilitated by the Linux Foundation, with the group being officially founded in December of 2022. Its founding members were Meta, Amazon Web Services, Microsoft, and TomTom, and today includes over a dozen companies as part of the group. This initial full release comes just a few months after an earlier preliminary release in April.

This is just the first step in what is an ambitious endeavor put together by some of the biggest companies in the world. To learn more about both this initial release as well as OMF more broadly, Geo Week News recently spoke with Marc Prioleau, the executive director of Overture Maps Foundation.

Bringing companies together

Prioleau, unsurprisingly, notes that it was not a quick process putting OMF together, which makes sense given the sheer size of the group’s founding members. He told Geo Week News about a “long incubation period,” noting that they are coming up on the two-year anniversary of the first internal reviews around forming what would eventually become OMF. For his part, Prioleau was with Meta prior to taking on the executive director role with OMF. He worked with maps within Meta, and was “very involved in putting together the group that ultimately became Overture.”

Despite the inevitable slow speed of any effort bringing together organizations of this scope, Prioleau does note “there was pretty strong alignment around the reason to make this happen.” Broadly speaking, there was agreement from all of these companies, and plenty of others, that maps which are derived from data for a variety of sources, which anyone can access, is the direction in which the industry needs to head. That, in turn, made keeping this group independent, even from the companies from which they were founded. That’s where the Linux Foundation comes in.

“The nice thing about the Linux Foundation is they provide you the scaffolding when you set up a foundation that allows you to focus on what you want to do, and not the other pieces. And the other thing is it’s independent.” Prioleau continues, “We very much want the project to be independent, and putting it in the Linux Foundation gives you a neutral turf.”

Who’s involved with OMF?

One of the curiosities around any group of this stature is who is actually doing the work. In terms of employees, Prioleau is the lone employee of Overture Maps Foundation, but he makes sure to point out there are plenty of others putting in the work. “We have some supporting marketing and legal teams, things in that structure. And right now, the rest of the people who are working on Overture are people who are members, who are coming in.” In other words, the organizations who are joining this group are, at least in some cases, offering people to do the work. He estimates there are around 130 engineers from various contributing companies, with people “gravitating to the teams they’re interested in.”

And in terms of those companies, a lot of current members fall into the geospatial realm in some form or another – companies like Esri, Nomoko, and Sparkgeo, for example – but anyone is able to join. “It’s an open organization, so various people can join, but we do emphasize contribution,” Prioleau said. “We’re asking people to come in and contribute, and contributions end up being in one of four ways.” Those four ways are financially, contributing data, contributing pipelines or technologies, and offering people and engineering resources.

These companies can join at one of three layers, steering, general, and contributing. Prioleau explains, “The steering layer is really around sustainability of the project. The people who are joining at that level are joining with the level of commitment that says we’re going to sustain this, because building maps is a long-term project. The next level is general, and that’s really where a lot of the work and decision-making gets made. And then the contributor level recognizes the fact that there are people who may not be able to join at a high level, but have data they could contribute.”

Openness is the key

The biggest thing that became clear throughout our conversation with Prioleau is how important the entire group believes openness is to their mission. Today, maps are largely dominated by companies like Google and Apple, without a truly open alternative that provides the same level of value. Providing that open alternative was the main ethos behind this movement, and why they ask any group member to have some sort of contribution.

“We really felt that open map data was a good place to push. There’s sort of a truism that maps are hard,” Prioleau notes. “But the real story of that is the next level, which is that map data is hard. If you think about maps as they’ve evolved from 20 years ago, where you got a map and what was on that map was whatever the mapmaker decided to put on there. Now, maps are this framework, and what’s really interesting is what you put on top of that.”

So where is OMF in terms of providing that data now? This initial release, as mentioned above, includes places, buildings, transportation networks, and administrative borders, all of which came from a variety of sources. For example, OpenStreetMap, a crowd-sourced open map, was used for large portions of the transportation network data. Buildings data was created using a combination of open data from the US government’s 3DEP program, along with data from companies like Esri and Nomoko. The places layer – or “theme,” as they call them at OMF – was largely put together using data contributed by Meta and Microsoft.

Data should only become more open as time goes on, too. “At some point people always ask me, where’s the line between open and proprietary? And my standard answer is: I don’t really know. It varies depending on who you’re talking to. But it only moves in one direction. It only moves up.”

Looking to the future

With any project of this size and scope, particularly one which is open to all different kinds of companies, it’s hard to clearly map out what the future could potentially look like. That said, Prioleau did have one definite answer as to what layer needs to be added next: Addresses. Beyond that, though, he believes members will drive the direction OMF moves in the coming years. If many automotive companies join, for example, there would likely be more work done refining transportation data.

He also, more broadly, looks to where the technology space in general appears to be heading, towards a “metaverse,” or more broadly spatial computing and things like mixed reality. “If you’ve got an augmented reality headset from one company, and I’ve got an augmented reality headset from another company, we need to share the same map. We need to agree that that 3D shape is there, and that digital asset is placed there in a certain way.”

And so, it all comes down to this idea of sharing data and creating open data, with which users and organizations can use it for whatever their application may be.

“If that framework belongs to a company, then there are pluses and minuses about attaching all kinds of other data to it,” says Prioleau. “But if that framework is open data, it becomes a shared resource, and now you really can open up the industry. There was this very strong feeling among the people we were talking to that open map base layers was really a key thing.”