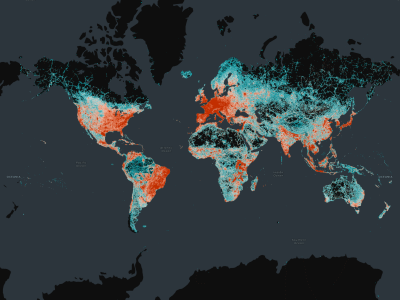

Late in 2022, a new organization was announced that had the potential to change the map data sector as we know it. Prior to the formation of the Overture Maps Foundation (OMF), whose founding members include the likes of Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, and TomTom, the map mapping industry was largely dominated by a small number of industry leaders, namely Google and Apple. The goal for OMF was to change that, promoting interoperable open map data. The organization describes their mission as follows:

“At Overture, our mission is to build reliable, easy-to-use, and interoperable open map data. We believe in harnessing the collective intelligence and resources of communities, organizations, and governments worldwide and aim to support a multitude of applications that drive innovation, enhance connectivity, and shape the future of our digital world.

We envision a world where the best maps are not proprietary assets but shared, open resources, built and enriched by the very people who rely on them.”

Since that official announcement of their formation in late 2022, the organization has made tremendous strides both in terms of output and bringing more companies into the fold. After starting with the four founding members, OMF is now up to 33 members as of last week, with a sampling of other members including geospatial companies like Esri, Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team, Precisely, and Nearmap, among many others.

In terms of output, they may have made their biggest announcement to date last week, announcing the first general availability of their map data. The general availability includes four themes to start – Buildings, Places of Interest, Divisions, and Base – with a fifth, Transportation, coming soon behind. In addition to the announcement of their first general availability, OMF also announced the addition of a new address theme entering an alpha stage, as well as a new explorer tool in beta for browser-based visualization of their data. To sort through all of this, Geo Week News recently spoke with OMF Executive Director Marc Prioleau.

Early on in our conversation, Prioleau lamented that it felt as though it took a long time to get to this point of their first general availability, but with acknowledgement that it’s not an easy process to get this kind of data ready for public consumption. He told Geo Week News, “Sometimes people say, How come you haven’t done this? How come you haven’t done that? But, which part of map data did you think was quick and easy?”

In a lot of ways, it’s a remarkable feat that OMF has been able to get to this point so quickly. That’s in part because creating map data is not as easy as it may seem, particularly in an open manner like this. They need to find open datasets from which to pull, and to put everything together in a way that makes it accessible for organizations across many different industries and localities. As Mike Harrell, a member of OMF’s Steering Committee, told us in a conversation earlier this year, creating the first 80 percent or so of a map is easy, but that last portion is significantly more difficult than one might immediately assume. That, really, is the reason these big companies aren’t building their own maps, but rather creating OMF in the first place.

Speaking of which, getting companies and organizations of this stature together for a collaborative effort is no small undertaking, but Prioleau notes that the engineers involved in this project have had nothing but positive things to say. He relays that one of the most common bits of feedback he’s gotten from these engineers since the release is that this is one of the “most fun” projects they’ve ever worked on. He says that since “everyone is a peer,” there is an energetic and collaborative environment formed where engineers from different backgrounds – both in terms of work area and where they live – come together under a common purpose, leading to a passionate workspace.

Getting back to this specific release, Prioleau says that it’s “always difficult with any sort of map data or geospatial data – you never have this feeling of: it’s complete. You always have this feeling that the world’s going to change tomorrow, and you’re going to have to fix it. Really, what we wanted to do was get to the place where we felt the schema was stable, and the Global Entity Reference System (GERS) was stable.”

He’d go on to explain that he breaks things down into data, the structure, and the schema. While spatial data is constantly changing, the schema should get to a point where it’s relatively stable and the pace of change slows down. Now that that’s started to happen, it becomes more stable and developers can more easily work with this data for whatever purpose fits their goals. For transportation, this process is a bit more complex given the number of attributes involved with it, which is why that is a little bit behind.

In our conversation, we also discussed the new address theme that has been released. For the initial alpha release, the theme includes data from 14 countries with a total of more than 200 million addresses. This data is pulled from openaddress.io, which in turn is pulled together from a number of different nation and local address data from around the world. Obviously, that is not all of the address data in the world – there are 220 countries worldwide – but address data can be tricky given that different countries present it differently.

“It’s clearly not all the data,” Prioleau said, “but one of the important things is - Can we take a bunch of countries from around the world, who all format their addresses differently, and come up with a uniform schema that will work on a global basis? When we do the address release, we’re not really testing the data. What we’re testing and putting out for public comment is the schema. At this point, that’s what we want to see how it works.”

Finally, in terms of the explorer tool, Prioleau outlines a couple of different goals with this recently released feature. One is to give potential users who might not have the engineering expertise of others a chance to visualize this data and see what it has to offer. The cloud-based tool is available for anyone and can answer some questions they may have about the data. Additionally, he says that the tool also gives users the ability to download the data as a GeoJSON file.

“What a lot of people have said is, I just want to look at the data, and by the way I want to bring it into my geospatial tools. Can I just get the data? So it gives a little bit of capability for that.”

This general availability release is clearly a big milestone for the organization, and one that came in relatively short time given all of the potential barriers that could pop up in this process. But now, it’s about having people actually use this data, and creating the tools necessary to spur adoption.

“People ask us what our main metric is. It’s obviously use,” Prioleau said. “A big piece of what we want to do is really build the developer tools. Sometimes people say, How come you don’t build this or that? And there’s a bit of a temptation to say, Well, it’s open data. Just go build it yourself. But our goal is to accelerate not only the building of the data, but the use of the data. It’s adoption, and if there are things we can do to spur adoption, that’s a good investment for us.”