THE HAGUE – Laser scanning is becoming increasingly commonplace in the oil and gas sector. But this is no time for hardware and software vendors to rest on their laurels and think they have “cracked” a challenging market, as a fascinating session from the “Industrial Facilities” track at SPAR Europe 2012 revealed.

This particular session featured presentations from two engineering service providers working in the hostile environment of the North Sea oil fields. First up was Iain Greenhalgh, British Petroleum AAD model manager and PDMS administrator with Wood Group PSN North Sea Ltd. Wood Group began limited use of laser scanning in 2006, slowly adding to its capabilities until in 2011 it acquired Production Services Network (PSN), thereby expanding its laser scanning software suite to incorporate Leica Cloudworx, as well as Microstation and PDMS, and adding an in house survey team, Spatial Solutions.

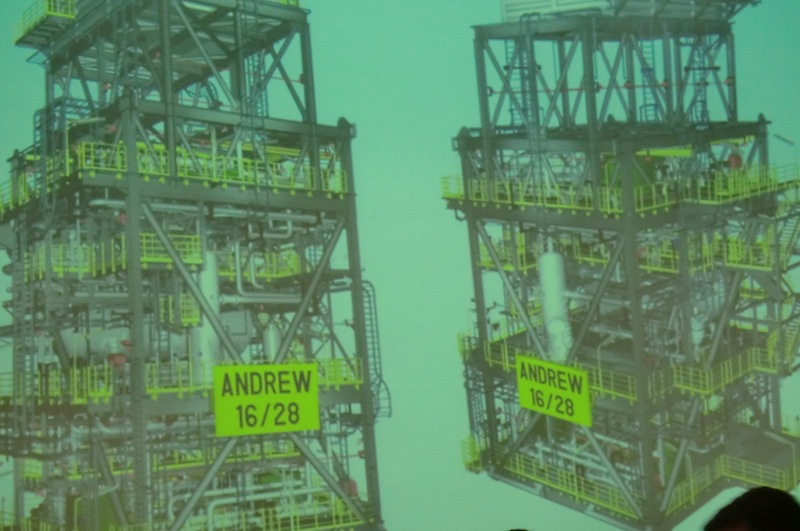

The company’s full capabilities have been put to the test by a contract to engineer new pipe, steelwork and electrical cable trays in real time for BP’s Andrew Area Development (AAD) project, a major retrofit of the Andrew oilfield. 3D laser scanning has been an essential tool in this process, which is still ongoing at the large brownfield site.

The first stage of the work involved an up-to-date and comprehensive laser scan conducted by the third-party survey company GDC, using Z+F gear. Around 90 percent of the existing plant was surveyed at the feed stage prior to contraction. Using a combination of LFM Server, Laser Modeller, PDMS and Microstation, Wood Group PSN’s designers were able to work on the 450+ scans in a real-time environment from multiple locations, with different engineering teams detailed to cover piping and structural features, electronics and instrumentation, and construction.

Piping and structural work primarily concerned the routing of new, clash free pipe and steelwork through a challenging network of existing pipes, steelwork and electrical cable trays. This included a full clash check, not just a “visual” clash check, noted Greenhalgh.

The scan data was also used by electrical and instrument designers to route new cable trays, junction boxes and cabinets and locate tie-in points to existing infrastructure. And, it was used in constructability reviews to identify hazardous areas, potential lifting issues, pipe and steelwork to be destructed and future tie-in points.

Greenhalgh pointed out how laser scanning led to a number of savings and process improvements, including cost and time savings, and reduced need for frequent offshore site visits and offshore bed space (very important to the client given the scale of the project). Other key benefits included accurate clash management and reduced risk – since most areas can be scanned without the need for additional scaffolding and specialist personnel, the potential for accidents offshore is reduced.

Most interestingly, he offered up a “future wish list” of four things that would simplify the engineering process once the scans have been made:

• The ability to reference the point cloud directly into the design software;

• PDMS to be able to recognise points in their native format, without the need for XGEOMS;

• A reduction in the file size of high-resolution point clouds; and

• Colour scans as the industry standard in the oil and gas sector.

An offshore scanning tale

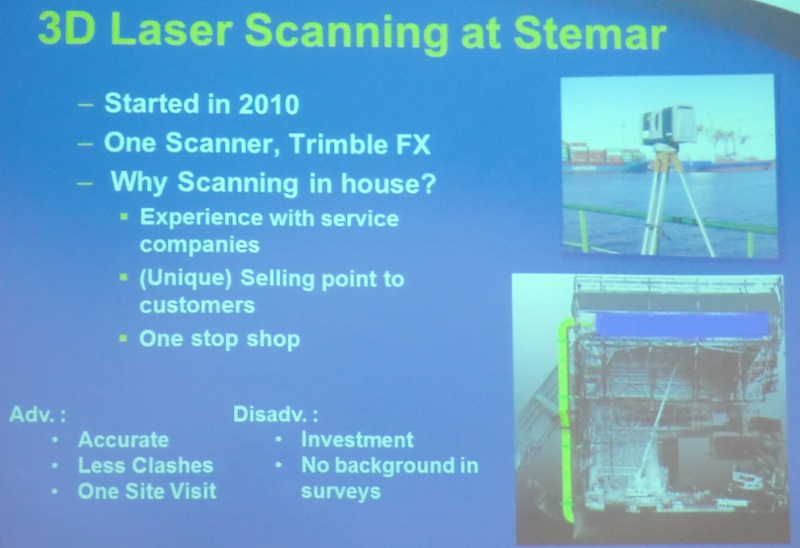

Second up was Mark Rood, owner of Stemar Engineering (BV), a Dutch firm that specialises in the iron and steel, production and construction and oil and gas sectors. Rood explained that the company is a comparative newcomer to laser scanning, having begun offering the service in 2010, with the purchase of a Trimble FX unit. Rood said that three factors were behind the decision to take scanning in-house: Stemar’s experience with service companies, the opportunity to offer a (unique) selling point to customers, and the desire to be a one-stop shop.

Being new to lidar meant that Rood’s presentation had a fresh perspective on the advantages and disadvantages of scanning in industrial situations. Stemar has used its equipment to scan high-pressure mud lines on a number of drilling rigs in the North Sea. The client was planning an upgrade to these lines to meet industry standards and requested a 3D scan because of the short installation time, the need for a quick and complete site survey, and the difficulty of welding high-pressure pipes onboard.

Being new to lidar meant that Rood’s presentation had a fresh perspective on the advantages and disadvantages of scanning in industrial situations. Stemar has used its equipment to scan high-pressure mud lines on a number of drilling rigs in the North Sea. The client was planning an upgrade to these lines to meet industry standards and requested a 3D scan because of the short installation time, the need for a quick and complete site survey, and the difficulty of welding high-pressure pipes onboard.

Rood focused on one sample offshore platform, scanned like all of the jobs that required a helicopter to transport gear with a very simple kit: The FX, a laptop, and 10 38mm spherical targets.

Working conditions were tough, with grease, mud, the risk of explosion (ATEX zone), lots of personnel in the areas being scanned and lots of stairs and ladders to negotiate. The ATEX zone is no small matter, either – because the FX is not ATEX-approved, Stemar had to acquire a permit and constantly monitor gas levels: “You have tests on your vest,” Rood said when asked about this separately, “and then the alarm goes off and you stop immediately and get away.”

In addition, the rig roofs were not accessible with the scanner and the two main survey areas – the rig floor and BOP area – were completely separate, with no possibility of registering scans into a single point cloud for a single rig.

Rood said that using the scanner has increased the accuracy of Stemar’s survey work, with fewer clashes and less time required on site. However, in future the firm intends to outsource the modelling of point clouds to India, “which is much cheaper and they can bring in much more detail to the models and save us a lot of time,” he explained.

No doubt this is an option that many other scanning companies will explore as the need for fast and cost-effective delivery of 3D visualisations increases.

Another modification they’ve had to make is swapping out targets that use magnets with targets that have suction feet. Magnets are no longer allowed offshore, Rood said.

Figuring out the workflow is worth it for Stemar, though, because the reality is that there are real benefits in the scanning and the work is only going to increase.

“One of the major [benefits]is the welds,” he said. “We’re talking about high pressure mud lines, 10,000 psi, piping of one inch thickness, and welding offshore is very difficult. You have to pre-heat the material, and it could take someone a whole day for two welds in the workshop. Doing it offshore, it’s more like two guys and only one weld per day. That creates a big savings in the installation time, and they have to install in between rig moves where they might only have a week or two weeks at the most.”

And there won’t be a shortage of needed welds and modifications, Rood predicted. “A lot of these drilling rigs are getting older and older, and the companies are prolonging their life cycle, so more and more revisions are to be expected,” he said. “There will be lots of work coming out of that.”