Laser scanning technology has seen rapid improvements in recent years, with just about every aspect of the equipment becoming more accessible. Sensors are now smaller without sacrificing power, making them more transportable and able to be used with alternative systems, be it as a payload on a drone, a terrestrial robot, or a handheld mobile system. They are also (relatively) cheaper, and the software is easier to use than ever before. As this accessibility continues to improve, more industries will start to utilize the tools to streamline their workflows and improve the quality of their work.

One space that is starting to utilize lidar scanners more than ever is law enforcement, a sector that is using reality capture to speed up and improve their forensics investigations for complex crime scenes. Given these tools’ ability to quickly create a digital snapshot of a scene with precise spatial context, it’s not difficult to see how that can be leveraged by law enforcement officials. And in fact, these tools are being used by police departments all around the world.

Recently, Geo Week News had the opportunity to speak about how these tools are being used in law enforcement with Bruno Costa Pitanga Maia, who works with the Brazilian Federal Police. Pitanga has been in law enforcement for 25 years, and has been leading a forensics team based in Brasilia who uses laser scanning in their investigations for the last four-to-five years. He notes that the Brazilian Federal Police have been using this technology for about a decade, and he shared with Geo Week News some of the benefits of the tools, the difficulty in getting greater adoption across the country, and some examples of how they leveraged these scanners.

Pitanga tells Geo Week News that, when the department first began using this technology in their tools, they started with tripod-based scanners from Z+F, but now have a larger base of tools with which they work. He called out a handful of specific tools they are using today, including a Leica RTC 360, as well as the handheld mobile scanners, the Leica BLK2GO, both of which are from Leica Geosystems, part of Hexagon, and can be used for larger-scale mapping. For smaller, individual objects, the Brazilian Federal Police also use scanners from Artec, including the Leo and Spider. Looking ahead, Pitanga shares that they are interested in using a scanner attached to Boston Dynamics’ Spot as well.

With all of that equipment, the benefits are clear to the teams that utilize the technology, significantly speeding up their work while also improving the overall quality of that work, with Pitanga saying they can “show things with the scanner that they can’t pick up without it.”

He also shared an example of how much quicker this work becomes when leveraging the scanning technology. “In one case we worked on in the past, we had more than 400 evidence tags on the ground. Usually, if you are doing a sketch by hand, you have to tie each of those pieces of evidence by hand, and use a measuring tape. Creating a coordinate system like that would take a week just for doing the sketch. Using a scanner, you can do that in half an hour.”

Despite all of these clear benefits, Pitanga relays that it’s still been difficult to convince other states within the country to more widely adopt this technology. Similarly to many of the other industries we cover that are starting to use this reality capture technology in their work, law enforcement is of course a well-established space with processes that have been in place for decades. It’s difficult to convince people in these circumstances to change the way they work, particularly if it’s been working, and even more so if, as Pitanga says, they are already lacking in the free time required to really learn about this technology.

Still, he does express an optimistic tone that attitudes are trending in a more open direction for a few reasons. One of them is that the technology is significantly easier to use. For example, he notes that when they first started using this technology about a decade ago they had to use targets for all of their scans, which was a time-consuming process. Now, they are able to complete their scans without targets. He also tells Geo Week News that younger people are starting to enter the department who are “willing to learn” about how to leverage these tools.

It’s a point that’s also backed up by Miguel Menegusto, a Geomatics Manager in Latin America with Leica Geosystems. Menegusto points to two key developments in this technology that has sparked more interest from those who traditionally have not used these tools. One is that they are now more mobile-friendly, resembling the technology most people now use in their day-to-day life. The mobile applications also allow users to see what has and has not been scanned while still in the field, rather than having to wait until returning to the office before seeing that data.

Additionally, portability has been a big development. Menegusto said, “The technology, over time, has become more portable and allowed this fit-to-purpose application where they can take it into more difficult environments.”

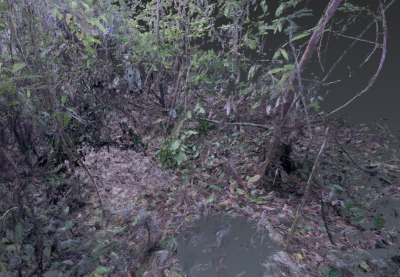

These scanners are generally used in the more complex investigations, as one would expect, and Pitanga gives a few examples of cases in which he has used the technology, including a high-profile murder of Brazilian indigenous expert Bruno Pereira and journalist Dom Phillips in 2022. More recently, a tragic plane crash in Brazil resulted in over 60 deaths, and Pitanga’s team was called to the scene to digitally capture crucial data with these laser scanners. In an article with Leica Geosystems, he goes into further details about the exact workflow his team has used in some of these cases.

Both in Brazil and around the world, we are still in the early days of laser scanning technology being a central part of forensic investigations. But as Pitanga has demonstrated over his half-decade of experience in the field, the benefits are clear and only improving. There is still a barrier in convincing long-time industry veterans to change their workflow, but as more evidence piles up for the technology’s value, and as these tools become easier to transport and use, adoption will only continue to increase, with investigations improving along with it.