In the aftermath of yet another Spar 3D, which saw yet another slew of new product releases, it’s interesting to see the way B2B media is changing coverage of laser scanning and 3D data capture in general. No longer do writers and commenters simply marvel at what laser scanning can do, maybe pointing to some pretty point clouds in awe. Rather, they are beginning to discuss laser scanning as a de facto tool that any professional in that particular business should have in their toolbox.

For example, take this piece in The Architect’s Newspaper, which explores the way Skanska is using laser scanning as part of its efforts on two large construction gigs in New York City. For those of us in the business, the use cases are pretty standard at this point. In one case, Skanska 3D captures a difficult-to-access job site and creates a 3D model that’s easy to virtually navigate so construction leads can lay plans and processes without having to actually put people in the space nearly as often or in large numbers. On the same job, they’re also using the scans to compare against historical drawings so that engineers and architects can understand the difference between what they think is there and what is actually there.

In another case, they’re using frequent scanning of new construction to make sure there aren’t deviations from the plan, so they catch errors early and don’t compound them. Check it out:

Sound familiar? Probably so if you’ve attended a Spar conference in the last decade.

But while early adopters and in engineering and laser-scanning focused publications were once the only places talking about these types of cases, we’re now seeing writers discussing this kind of technological adoption almost a matter of course:

This interoperability and ease of use, along with significantly reduced cost, have turned laser scanning from a pricey gimmick into an almost necessary tool. “There’s a right time and place for technology, and both Moynihan and La Guardia are benefited by that,” said Zulps.

If every scanner manufacturer isn’t taking the first sentence of that quote and making it into a bumper sticker, someone in the marketing team needs a talking to. That’s gold, Jerry.

Outside Construction Work, Too

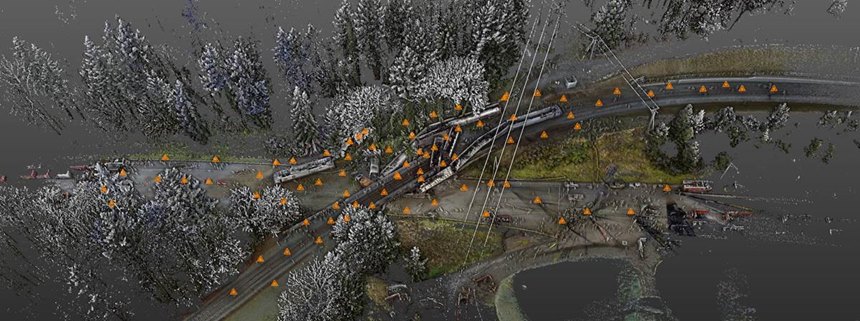

And it’s not just construction, which is obviously top of mind for those who were at the AEC Next event co-located with Spar. Scanning is also becoming par for the course in police work, according to a piece in Police One (which is, admittedly, sponsored by a UAV manufacturer, but still seems genuine). So par for the course, in fact, that Washington State Patrol isn’t just terrestrially scanning crash sites, but using a UAV to grab overhead scan data and combining the point clouds to create huge 3D visualizations they can interrogate in a number of ways.

Look at the similar way this author describes scanning and point cloud use:

Indeed, Gunderson’s penchant for experimentation has been key to becoming at ease with technology. Case in point: soon after acquiring his first UAV, Gunderson tested the possibility of merging scan and UAV data of the same scene into one, integrated point cloud. It was not only a success, but the integrated forensics view has become a formidable tool for accident reconstruction cases, which make up 65% of their responses.

It’s incredible to think of how far technology has advanced in so short a time, to the point that the Washington State Police can take 82 terrestrial scans and a mile worth of UAV-captured photo data and have a full point cloud of the accident scene completed in 36 hours. Heck, just getting 82 terrestrial scans done between an 8:30 a.m. accident and 2 p.m., when they left the scene, is pretty dang impressive.

Nor is this kind of tech deployment only for giant train crashes that make the national news:

WSP also launched a UAV pilot program last July and outfitted 15 collision-technology specialists across the state with smaller UAV units. The aim was to assess whether the technology could help them map straightforward accident scenes more efficiently and accurately. Soon after the pilot began, a team responded to a one-car pedestrian accident on I-5. Prior to the UAV, they would have worked the scene for a few hours with traditional baseline methods. Using the UAV, they cleared the scene in 18 minutes.

“Someone from the state DOT (Department of Transportation) once told me that any time the I-5 is shutdown, the cost to the region is about $350-$400 a minute,” Gunderson said. “That adds up to a big number really quickly.”

So, to do the actual math there: That’s roughly $6,300 of regional impact versus about $63,000. Which will get people’s attention, for sure.

But if 3D data capture is now just a matter of course for many, how does that change the marketing and discussion of the technology? How does that change what people might be willing to pay for it? How does that change the way these tools will be operated and by whom? What will separate true professionals from those who are just pushing a button and seeing what happens?

These are major questions the industry as a whole will now have to focus on for the industry to truly take advantage of changing perceptions of what, not that long ago, was a “pricey gimmick.”