Generally when we talk about reality capture here, we are talking about its usage as part of an inspection, construction, or design workflow, with the technology often utilized as payloads on UAVs, vehicles, or robots – though not exclusively. One of the other important uses of this work however, is for conservation and restoration purposes. We’ve seen reality capture used, for example, in Ukraine to have accurate models of culturally significant buildings in case they were damaged or destroyed in the war with Russia, and to create a 3D archive of a former gold rush town which can be viewed remotely and create an accurate record if/when the area continues to deteriorate from natural wear and tear.

In London, a similar project has been underway for the last few months to create accurate 3D, digital models of the famous Crystal Palace dinosaurs. The project was undertaken by Historic England, a national program charged with protecting, championing, and saving historically important places and structures – around 400 properties total – around the country. Jon Bedford is a Principal Geospatial Surveyor and Team Leader with Historic England, and led the team tasked with creating the models. Bedford recently took some time to speak with Geo Week News about the project.

What are the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs?

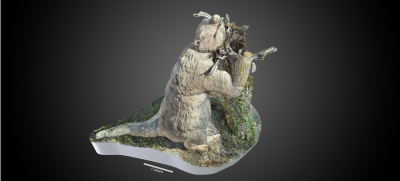

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, while scientifically inaccurate, are certainly historically significant as what are believed to be the first-ever live-sized models of extinct animals. Commissioned in 1852 and first unveiled in 1854 – only about a decade after the term “dinosaur” was even coined – the dinosaurs were sculpted by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins to accompany the Crystal Palace after it was moved from the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park to Crystal Palace Park in Bromley, a borough of London.

Despite being referred to as “dinosaurs,” not all of the sculptures are actually dinosaurs, with prehistoric mammals being represented as well. Today, though, they are particularly notable for their inaccuracies, giving a glimpse of what the scientific community viewed as truth in the mid-1800s. While there have been extensive restoration efforts over the years – sculptures over the years have lost snouts and jaws, for example – the inaccuracies have remained. In 2007, the structures were classified as “Grade I,” the highest rating of historical significance a listing can get. Per Historic England, only 2.5 percent of listed buildings are classified as Grade I.

Inside the creation of Historic England’s Models

In speaking with Bedford, it’s clear that this isn’t exactly like the projects he and his team – which includes himself and three other team members – typically take on in a number of different ways. For one, he explains that their “main focus is heritage buildings and structures; those can be buildings and structures that are at risk of collapse due to a lack of maintenance, all those sorts of things.” Typically, that work is done cyclically on an every-five-years basis.

This project came about a bit differently, and is not on the same quinquennial schedule, but the purpose of the work was largely the same. Most of the projects this team works on are with buildings and structures owned by the English Heritage Trust, but these are owned by Bromley Council.

Bedford said, “It was clear that the conditions survey needed doing. Bromley Council knew it, Historic England knew it, everybody knew it needed doing. Then it was a case of: How do we facilitate this? As it turned out, the easiest way to move things forward was for us to complete our surveys.”

As far as the actual workflow goes, Bedford explains it was a hybrid process combining the use of laser scanners with photogrammetric techniques. He told Geo Week News, “The first step was establishing some control across the site with GNSS Control. Then, we used a framework of scanning using the Leica RTC360. We weren’t scanning each of the dinosaurs in detail, but were making sure that there was a good portion of each one across the scans.”

That scan data was then used as a control for the next step: photogrammetry. Bedford said, “Each of the models is photogrammetric, but we were pulling in the scans that were relevant to each particular dinosaur so we had position, scale, orientation, all of that stuff from the scanner data.”

The team then used Capturing Reality and AgiSoft Metashape to process all of the data. “So we’ve got scans and images,” Bedford explained, “and we’re producing these hybrid meshes, texturing them. That was how we produced this set of models. It’s this combination of laser scanning and photogrammetry, and the laser scanning is properly controlled so that everything’s in the right place.”

Bedford had a hard time nailing down an exact timeframe for the workflow, as it wasn’t a totally linear project – they had to be pulled away for other things at times – and there were trips back and forth to refine the model and capture more images. That said, he estimates that in total it took six days on-site for scanning and photogrammetry, and then an additional three months or so for processing and updating the models.”

How are the models being used?

The purpose of these models largely falls into two buckets: conservation and “edu-tainment.” On the former point, it’s similar to myriad other restoration and conservation projects around the world. These models provide an accurate digital record of the individual structures, which are used to plan and execute on restoring them to their original state. “They’re being replaced with a sort of GRP [Glass Reinforced Plastic] or 3D printed light materials.” The models are providing the basis from which the restorers can plan their renovation efforts.

Beyond the conservation piece, though, these models have also been released publicly so anyone around the world can interactively view them. Each of the structures’ models are housed on Sketchfab and can be accessed here. This use case is, in fact, a nice tie-in to when Hawkins originally created the sculptures, as one of the original goals was to create a fun and interactive way for local children to learn about prehistoric history. Today, Bedford says, “the online model collection is a kind of portal for people who can’t get to London to be able to still see these sculptures.”

In a press statement, Simon Buteux, Partnerships Team Leader at Historic England, highlighted this as well, saying: “The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs were a milestone in the public outreach of science when they were first created, and they still have admirers near and far. Our new models will let even more people get to know these wonderful prehistoric beasts. The scans will also help us to better understand the sculptures’ conservation problems and aid with their restoration.”