The war in Ukraine has already taken a nearly incalculable toll on the people and infrastructure of the country. With millions displaced and thousands of lives lost, it will be a long road to recovery for the beautiful nation, rich in history and culture. In addition to the human toll of the conflict, the threat of destruction for the country’s oldest and most significant cultural places and objects is real - and ongoing - as long as the war continues.

As of the end of May, the Ministry of Culture and Information Policy of Ukraine (MCIP) has identified[1] at least 367 incidences of destruction at cultural sites to date, including the destruction of 29 museums, 133 churches, 66 theatres and libraries, and even a century-old Jewish cemetery - all of which would be considered war crimes.

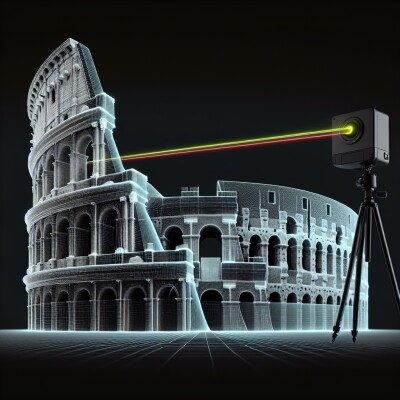

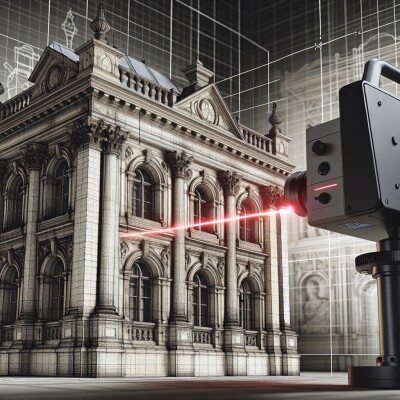

In an effort to get ahead of this potentially massive loss, co-founders of a laser scanning and photogrammetry company, Skeiron, are leading a charge to capture as much of the country’s cultural heritage as possible using laser scanning and photogrammetry tools at hand, through a project called #SaveUkranianHeritage

Geo Week was able to connect with Yura Prepodobnyi and Andriy Hryvnyak, two of the co-founders of Skeiron, to hear more about their efforts to apply their skills and technology towards an important purpose: to capture - in as much detail as possible - the cultural relics of Ukraine that are threatened by war.

Common interest becomes a common cause

Long-time friends and classmates going back to childhood, Prepodobnyi and Hryvnyak went to the same university, studying in different, but related areas. Hryvnyak and Volodymyr Zaiats (not present for the interview) focused on computer science and engineering in their studies, while Prepodobnyi studied surveying and geodesy, including the use of laser scanners, total stations, and photogrammetry, and eventually to learning how to fly drones to take photogrammetry from the air. The group did a lot of photogrammetry and image capture in their spare time to learn how to get better at the art of it.

“We bought our first drone and the first thing we did was crash it right into the ground,” laughed Prepodobnyi.

Their drone piloting skills improved with practice, as did their abilities to capture buildings and scenes. When they first scanned their university campus, and weren’t happy with the result, so they continued to learn and improve with each attempt. When their professors discovered they had a drone, the professors involved them in their research for volume measurements, for use in things like mining.

“When we finished university, we had a lot more practice than others - we had already worked with drones and a DSLR camera,and had done some laser scanning” said Prepodobnyi.

When the group started their own company and wanted to market their services, they found that not a lot of potential customers understood what the models could look like. Their co-founder suggested creating augmented reality models from the buildings they’d already scanned - which they quickly made into brochures so that people could look at the models immediately.

When the group started their own company and wanted to market their services, they found that not a lot of potential customers understood what the models could look like. Their co-founder suggested creating augmented reality models from the buildings they’d already scanned - which they quickly made into brochures so that people could look at the models immediately.

This lead to a project called “Pocket City” - where a series of postcards were created to showcase local sites of interest through augmented reality. Their local Ukrainian Cultural Foundation then encouraged them to expand the project by applying for grant money. Over the next three to four years, they produced resources for several regions and cities - not knowing that this would eventually lead them to their latest endeavor.

From postcards to preservation

The war in Ukraine has been disruptive to all aspects of life for Ukrainian citizens, including groups already attempting to preserve heritage sites. Local governments and cultural/tourism departments were suddenly desperate to accelerate the process of digitizing their assets. The team at Skeiron has been concerned about the fate of Ukraine’s cultural heritage for years, and their new calling is to digitally save as much of Ukraine’s architectural and artistic heritage as possible.

The war in Ukraine has been disruptive to all aspects of life for Ukrainian citizens, including groups already attempting to preserve heritage sites. Local governments and cultural/tourism departments were suddenly desperate to accelerate the process of digitizing their assets. The team at Skeiron has been concerned about the fate of Ukraine’s cultural heritage for years, and their new calling is to digitally save as much of Ukraine’s architectural and artistic heritage as possible.

At the beginning of the war, they started to scan objects located in Lviv, some that were very culturally valuable and had not been captured before.

“Across the country, Ukraine also has thousands of wooden churches, which are especially vulnerable to fire, and many also have important paintings in their interior - which is why it is important not only to laser scan them, but to get high-quality photogrammetry as well.”

For this effort, the team at Skeiron has been working with local government officials to generate and prioritize a growing list of targets, and to track their progress, says Prepodobnyi. The company has two laser scanners on hand - a Leica C10, and Leica ScanStation P20 - as well as a pair of DLSR cameras and an off-the-shelf drone, used when they are given permission to fly over a particular building.

“After the discussion with the government officials, for example, the Department of Culture and Tourism for the region, we speak to our partners in other regions who might be able to do laser scanning or photography, then combine our staff, or coordinate getting the scan completed.”

Luckily, there has been a slight reprieve in the violence in some areas, which has allowed the team to do more in-depth and high-resolution scans than their first attempts, which were urgently being performed, sometimes only in a day or so.

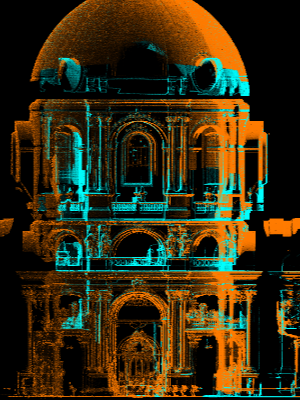

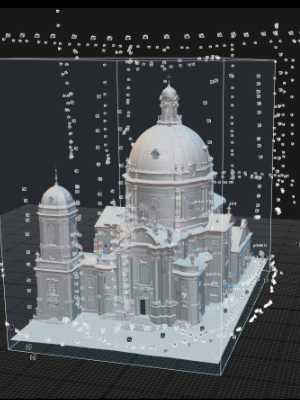

Beauty in the details

The scale and the detail of some of the projects is massive and would be impressive even if accomplished in peacetime. For a UNESCO-protected church in Lviv, Ukraine, more than 300 individual laser scans were needed, and 5-6000 photos were stitched together for the final, breathtaking project.

Click to enlarge the pictures below:

|  |  |  | |||

|  |  |  |

What happens when the dust settles?

While 3D scans have proved helpful in reconstructions of other heritage sites, for example, when the Cathedral of Notre Dame was lost in a fire, or the Kumamoto Castle in Japan was struck by an earthquake. In Ukraine, however, the grim reality is that the war-torn country’s priorities may delay or prevent restoration from ever happening for some of these sites, explains Prepodobnyi.

While 3D scans have proved helpful in reconstructions of other heritage sites, for example, when the Cathedral of Notre Dame was lost in a fire, or the Kumamoto Castle in Japan was struck by an earthquake. In Ukraine, however, the grim reality is that the war-torn country’s priorities may delay or prevent restoration from ever happening for some of these sites, explains Prepodobnyi.

“In the near future, we will not have the funding to reconstruct those objects coming from the Ukranian ministry - it will be necessary to fund the army to protect the country. Because of this, scanning is just our way to preserve that object for the future, and for future generations.”

To Skeiron, though, this effort is both for the hope that these relics can one day be restored - but also the realistic knowledge that these scans and virtual experiences may be the only thing that future generations are able to access.

Through collaborating with others and partnering with local cultural ministries, the group hopes that they can accelerate the efforts underway, both now - in the midst of war - and in the hopefully more peaceful future.

Getting involved

A note from Skeiron: Skeiron hopes that people will spread the word about #SaveUkranianHeritage, as well as take in and appreciate the relics already captured. They are in need of additional funding, as well as scanning and photogrammetry equipment - so if you can help to connect them with additional materials or equipment, they encourage you to contact them either through LinkedIn, email or phone +38(093) 826 38 50. More information is available on the project website.