You can’t have a conversation these days about anything coming close to touching the tech world without it eventually – and usually quickly – getting into artificial intelligence. Largely driven by large language models like ChatGPT, AI has taken the consumer world by storm, and thus has dived headfirst into the mainstream consciousness. Like every other industry, geospatial is seeing a boom in AI in terms of everything from funding to capabilities to the sheer number of offerings. Companies are adding these algorithms into their workflows, and whole companies are being successfully launched on their backs, streamlining some of the most arduous and complex aspects of what professionals do on a daily basis.

One such company is a relatively new one in Flai. Based in Slovenia, Flai works with large point cloud data sets, building technology to automate information and sharing within the geospatial industry. Recently, Geo Week News spoke with Nejc Dougan, Flai’s Chief Technology Officer and co-founder, about what the company provides using AI, as well as the current and future use of the technology in the industry as a whole.

Dougan began really digging into this concept while working with Flycom Technologies, a remote sensing, GIS, and consulting provider. While there, he also worked towards a PhD in computer vision and AI. One of his early jobs at Flycom was to manually annotate point cloud data captured by the company, which he says was “sometimes quite a frustrating task to do.” Eventually, he started working with the company to optimize processes which would be able to automatically complete this often tedious work. Using AI and computer vision algorithms, they began to see success, and eventually he and co-founder Luka Rojs spun off from Flycom to start providing these services to other clients.

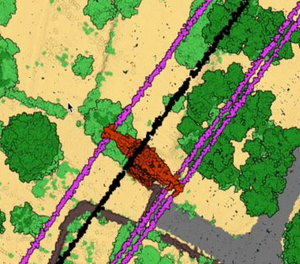

The company, which started early in 2022, began largely serving clients based in Europe, but has since grown to serve a more global customer base. From the start, the primary focus for Flai in terms of industry has been for large lidar mapping datasets, but they also work in sectors like mining, infrastructure, power line inspection, maritime, and most recently have started to see an increase in the demand for forestry-related projects.

Dougan notes that they can fairly easily add more use cases to their repertoire as well, saying, “One of the strong points of the AI is that we can quite quickly adapt our algorithms to new use cases, and therefore our clients can create new training datasets and retrain the AI for themselves via our web application, and we also offer service to do that for them or consult them on how to do it.” That ability to add more use cases, giving them a large number of assets they’re able identify, is what Dougan says separates them from other AI providers in the industry.

In addition to discussing Flai, Dougan also spent a little time speaking with Geo Week News about AI in general and how it’s being used in the geospatial world. He recognizes that we are still in the relatively early stages of truly harnessing AI in the industry, but says already that there are big needs being met and workflows being enhanced. Specifically, he points to simply the amount of time, and thus money, that is saved by doing things like point cloud classification via algorithms rather than relying on manual labor. Ultimately, he says, “this could open up new use cases that weren’t possible before.”

Within any conversation about artificial intelligence – in any industry, not just geospatial – one of the main concerns is the fact that these algorithms could ultimately replace and displace human labor. It’s a fair concern, and something already being used as leverage in, for example, the WGA’s strike. That said, the imminent fear of this is more of a concern in some industries than others, so we asked Dougan how he felt about that specifically with this kind of work.

His answer was that it’s not much of a concern right now for a couple of reasons. One is that there is simply so much data that it can’t all possibly be processed by humans anyway. “Even if we will be optimizing 90 percent of this data,” Dougan says, “we still have so much data we need to process.” Additionally, at this point the algorithms still are not at a point where they’re accurate enough to be run on their own. Human intervention is still necessary for quality assurance, and it’s not clear we’re all that close to that need going away.

There are still improvements to be made with AI looking towards the future, and not just in terms of accuracy within their current use cases. We asked Dougan what he believed may be done using these algorithms in the next couple of years that isn’t possible today, and he pointed towards use cases in which constant streams of data must be processed. He mentions that many mapping projects are now being done with mobile mapping systems that are constantly capturing data. It’s not possible to manually annotate this data, but suggests that at some point in the future these algorithms may be able to complete these tasks.

.jpg.small.400x400.jpg)