Earlier this year, I was talking with a service provider who specializes in mass transit. They do lots of roadways, railways, bridges, and that sort of thing. Essentially, they found themselves documenting “corridors,” big long stretches of not just the surface along which something would travel, but also the vegetation, surrounding buildings, underlying waterways. Giant tubes, really. Many firms do similar work.

As you might expect, they were using a mobile mapping solution. But their days of setting up terrestrial scanners aren’t exactly over. There are inevitably shadows, corners they want more data on, etc., so they still find themselves out there grabbing scans one by one. And then they’re also sometimes needing scour information on bridge pilings and pulling in bathymetry. Heck, sometimes they find aerial lidar handy for larger projects.

And they always fly a UAV to get great orthophotos for baseline information, presentations and cool fly-through videos.

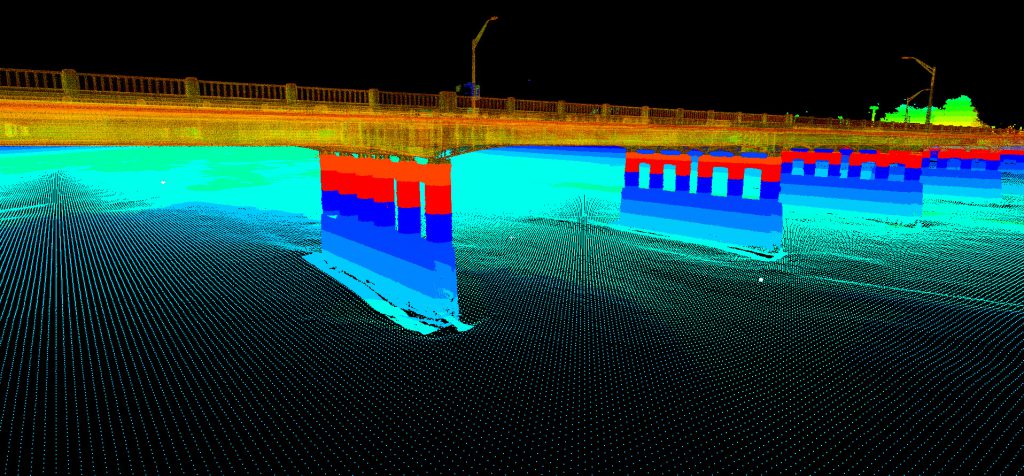

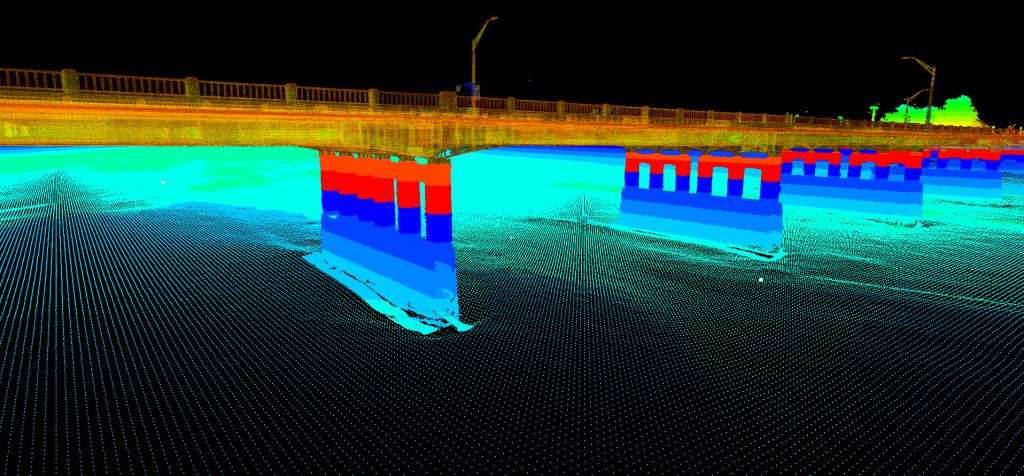

Spicer Group and Horrocks Engineers combined terrestrial and bathymetry data in a single point cloud.

Of course, all of this is possible because so many of the software and hardware manufacturers are offering good, standardized options for pulling in data from a variety of devices into one cohesive point cloud and/or visualization.

But that same service provider noted one ironic thing: They’re deliverables haven’t really changed at all. They’re still delivering DoTs the same basic 2D as-built documents they’ve always delivered. And my guess is that’s what’s holding back real innovation in the integration of multiple technologies. Ultimately, if it doesn’t deliver added value for the end user, it doesn’t deliver more revenue for the service provider, and the incentive for innovation isn’t there.

Right now, the industry seems to be in a place where service providers know there’s a lot more they could do, but they lack the incentive to do it. Where might that come from?

First, it’s going to come from getting away from hourly rates and focusing on overall project costs when making proposals. If the varied technologies can allow for the same deliverables to be created in half the time, but still get you the same revenue, then that reduction in person hours can quickly deliver a return on the investment in your new technology. Some people argue that you’ll just be trading field hours for desk hours, but that seems overblown, and your desk hours are probably cheaper and safer, anyway.

TrueScan used drone footage to document existing features and plan terrestrial scan routes.

Second, it’s going to come from end users having the tools to use better and more interesting deliverables. They need relatively inexpensive, browser-based solutions that allow them to repeatedly interrogate their data and see the long-lasting value it provides. Can they reduce their own field hours? Can they gain insights that increase performance or decrease their annual spend?

Third, it’s going to come from end users seeing these deliverables as daily-use tools as part of their ongoing operations, instead of snapshots in time that are only meant to support specific projects. What if you could provide monthly mobile mapping that created delta maps identifying potholes and automatically suggesting efficient routes for addressing them? What if you could provide monthly vegetation-encroachment maps, giving them a plan for chopping back vegetation that might cause delays in service?

These are things that might create some serious demand. As yet, I haven’t heard anyone doing this kind of partnership work with their end users with ongoing data collection agreements. But it’s coming. I’m sure someone’s doing it. We’re definitely seeing way more case studies that involve multiple tools for data capture.

Back in May of 2019, TrueScan released a nice piece about their work with the Veterans Administration and eight different health care campuses. It’s a great mix of documentation, UAV, and terrestrial work.

And in October of 2019, I reported on a cool piece of collaboration that combined mobile, terrestrial, and bathymetry to start a bridge rehabilitation process in Idaho.

And check out this combination of laser scanning and photogrammetry for use in documenting the anatomy of various biological specimens!

Of course, many service providers have been experimenting with this sort of multi-tech reality capture for a long time. You can find academic papers along these lines going back to the early 2000s. But now we’re seeing it in the field and producing results. Maybe 2021, a year I expect some serious innovation to pop in a number of areas, will be the year we really see it become the commercial norm.