Current 3D printers are pretty great if you want to print a coffee mug or a bobble-head. But what if you could print more complicated objects using more than just a single material? I don’t know about you, but I can only fit so many mugs in my cabinet.

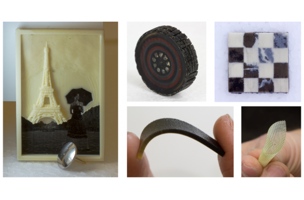

Now, a group of researchers from the reliably groundbreaking institution MIT have developed a 3D printer named MultiFab that can print with 10 different materials at the same time. They claim that this ability, coupled with the unprecedented low cost of the device, will “dramatically expand” the number of things that you could conceivably print.

It might be a glimpse of a consumer 3D printer that would actually be useful. Think of it: you could soon be printing complex mechanical, electrical, chemical, and optical objects. Want to print a digital camera? Sure!

What’s surprising is that this isn’t even the biggest advancement that MIT made with MultiFab.

The group at MIT that worked on this printer was the Computer Science and Artifical Intelligence Lab (CSAIL). I note this because they are not a materials science lab as you might expect, but a group working on computer intelligence like machine vision. Indeed, a key part of the printer is an “integrated machine vision system” that “allows for self-calibration of printheads, 3D scanning, and a closed-feedback loop to enable print corrections.”

The printer works by printing one layer of material on top of the other, just as any old 3D printer would. However, a small proprietary 3D scanner in printing head scans the levels as they print to compare them to the design. Think of it as comparing the as-built to the design—but on the level of the object rather than a building or bridge.

When the as-printed object is missing parts, the printer re-calibrates and prints a correction. This feedback loop allows the printer to print at very high resolution.

As you’ll see in this video, the 3D scanner also enables the printer to print on top of existing objects. Place an object into the print area, the 3D scanner takes its dimensions, and then prints around the object. In the video, they show a handle that they’ve printed on top of a razor blade. Imagine the possibility for repairs.

For those of you who want to know the technical dirty details: the 3D scanning head was built using an “optical coherence tomography scanner.” (It’s a bit too scientific to explain here, but if that piques your interest you might find the research paper enlightening).

The researchers at MIT selected this technology for the printer for a few reasons that highlight the difficulty of using 3D scanners for such specialized purposes. Since the printer resolves each individual printed layer at 40µm or less, the team explains that they needed a 3D scanning technology that could operate at a resolution of 10µm or less. Since at this scale all materials become translucent or semi-transparent, “stereo, structured light scanning, shape from shading, etc. cannot be used.”

All of which means they had to get creative. Good thing for us they were up to the task.