By Eugene Liscio, P. Eng.

There are any number of reasons why someone would want to use thermal imagery: to check for leaking pipes, to look for cold or hot spots at industrial plants, or to optimize the thermal efficiency of a structure. However, the use of thermal imagery at crime scenes has never been widely adopted. This is interesting because it would fit in with so much of what is being done in forensics, which involves detecting and bringing to light what cannot be readily seen by the human eye. For instance, investigators can find blood, semen, and gunshot residue where it is very difficult to see by using ultraviolet, infrared, and fluorescing chemicals.

Heat is a special kind of evidence because it decays relative to ambient conditions and with time. Since time is a critical factor in an investigation, and heat can say something about time, it can be an important piece of evidence in an investigation. Heat can say something about the crime itself. So, why not look for evidence such as a warm handprint, a hot cup of coffee, a cold beer, or a car engine that is still warm?

In order to gather this potentially helpful evidence, an investigator would need to use thermal imagery. This is because heat will not be immediately evident to an investigator who walks into a crime scene, as humans have a limited sense of heat detection (also called “thermoception”). A person needs to be relatively close to an object, or needs to physically touch the object to determine if it is hot or cold.

Figure 1. A handprint becomes clearly visible when a thermal image is applied to the point cloud.

Here’s an example of how thermal imaging could help us to understand crime scenes better. A few years ago, I saw a student research presentation at the University of Toronto, Mississauga that was looking at detecting objects behind walls by using thermal imagery. The concept was rather simple: Deliberately change the temperature of a room by adding heat or by removing it (perhaps by opening windows in the evening), and as objects begin to heat or cool at different rates, they can be detected even if they are behind walls. So, things like weapons or someone’s “stash” could be found a lot easier, and without the need to guess and tear down walls.

There are a few signs that thermal imaging may still catch on within forensics. At the last SPAR 2014 Conference in Colorado Springs, Z+F displayed their latest addition: a thermal camera mounted on top of their 5010C laser scanner. Although thermal images are not new to laser scanning (Riegl has an integrated thermal camera system and FARO users have also combined thermal images with scan data), it was the first time that anyone thought of using a thermal scanning system at one of our IAFSM workshops.

Figure 2. Z+F 5010C with thermal camera attachment at IAFSM Workshop at SPAR International 2014.

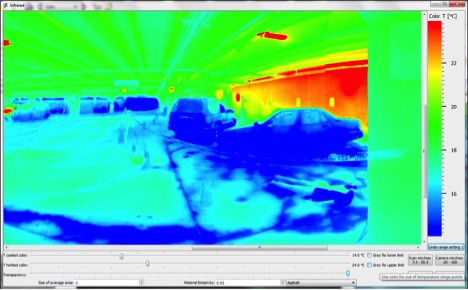

Figure 3. A thermal image taken by the Z+F system at the IAFSM Workshop during SPAR. The dummy in the bottom right has a hot and cold side. Did someone roll the dummy over?

A fusion of laser scanning data and thermal imagery makes sense. Laser scanning data can already be viewed as intensity based on a wavelength of light, usually in the near infrared range. So being able to visualize a crime scene with alternate types of light radiation/spectra may even help us to perceive and analyze a crime scene in new ways.

Figure 4. Simulated crime scene with thermal images. (With permission by Jonathan Coco)