It’s no secret the military is using 3D data capture in a number of applications, but a few articles that have been popping up about the use of lidar in Afghanistan got me focused lately on how the technology is being used specifically in that military theater. Quite simply, it’s being used a lot. Particularly, lidar mapping has become very popular with the people on the ground there.

Combing through the collected literature, it would seem that the military’s use of lidar in Afghanistan is one of the technology’s real success stories.

What sparked my interest initially were two articles (essentially the same articles, with different first paragraphs to suit the different sites he sold the article to) by David Walsh that popped up this week:

Defense Systems, “Warfighters reap benefits of LIDAR mapping technology”

Government Computer News, “Laser-based mapping tech a boost for troops in Afghanistan”

There’s an awful lot of explanation of what the technology is, and some treatment of how it’s being used, but it’s the second-to-last paragraph that’s really the nut of the story:

An NGA imagery scientist, who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons, said that depending on the mission, LIDAR sensors are “bathymetric, topographic and atmospheric … and gather topographic data using different regions of the spectrum.” The resulting data is used to automatically generate high-resolution 3-D digital terrain and elevation models. Overall, the scientist said, LIDAR elevation data supports improved battlefield visualization, line-of-sight analysis and urban warfare planning.

I’d think that maybe should have come earlier in story, since that’s where the benefits are being reaped.

Anyway, looking to learn more about lidar’s use in Afghanistan I began to come across a treasure trove of information. Probably a better overview of how lidar is being integrated into systems over there comes from Peter Buxbaum in an October 2010 article in Geospatial Intelligence Forum.

It’s an excellent article with a number of great real-world examples of how the technology is being used – certainly worth the 20 minutes time to get through it. As just one example:

The detailed mapping of urban and non-urban terrain can bring other benefits to warfighters as well, noted Tom Lobonc, director of defense products at ERDAS. “Having a detailed urban surface model is beneficial to identify lines of sight, which are critical for a variety of tactical applications,” he said. “For example, LiDAR has been used to identify suitable observation posts, locations for cover and concealment during operations, and sites for locating communications transmission and interception equipment.”

Essentially, when you’re talking about lidar for mapping in Afghanistan, there are two main programs in place. The first is Buckeye, which has been active since at least 2004. Here’s the fact sheet on that. Essentially, it’s a way of collecting unclassified high-resolution geospatial data for tactical missions. In Afghanistan, the data is collected by a UAV, with a “miniaturized lidar sensor,” but Buckeye is also active in Iraq and stateside.

More recently, DARPA created HALOE (High Altitude Lidar Operations Experiment), which “is providing forces in Afghanistan with unprecedented access to high-resolution 3D data, collected at rates orders of magnitude faster and from much longer ranges than conventional methods.”

Even better, DARPA is now using that data to create 3D holographic images of urban environments, which soldiers can use to visualize the areas they’re about to enter. They announced the program in March, but have probably been using it for a little while longer than that, I’m guessing.

Certainly, it’s something DARPA is proud of. In recent testimony before the Armed Services Committee, DARPA head Regina Dugan was singing the program’s virtues:

The high-altitude LIDAR operational experiment system, called HALOE, can collect data more than 10 times faster than state-of-the-art systems or 100 times faster than conventional systems, Dugan told the panel.

“At full operational capacity, the HALOE system can map 50 percent of Afghanistan in 90 days,” the director said, “whereas previous systems would have required three years.”

How’s that for an endorsement of the technology?

But it’s not all about airborne lidar mapping.

Gizmag back in December put out an awesome piece on Lockheed Martin’s Squad Mission Support System, a semi-autonomous vehicle (see accompanying picture) that uses lidar to navigate and basically serve as a pack animal.

How cool is this:

In autonomous mode, the SMSS uses a 3D scanning LIDAR to navigate its immediate surroundings while following either the optical form of a certain soldier or predetermined way-points (which can be set by the operator or can be automatically dropped by the SMSS during allowing a trace back mode).

This technology is said to help decrease the amount of time a warfighter has to spend in controlling robotic systems, by providing vehicles with a greater perception of their surroundings on the battlefield.

The things basically use what looks like a Velodyne sensor to follow soldiers like hyper-obedient mules, taking off some of the 100 pounds of equipment that modern soldiers are expected to carry at all times in the field.

That’s just brilliant.

They also used terrestrial laser scanning as part of the facsimile of Bagram Prison they’ve been making since early 2010. I’m not sure that workflow is any different than standard stateside scanning for historic preservation, though.

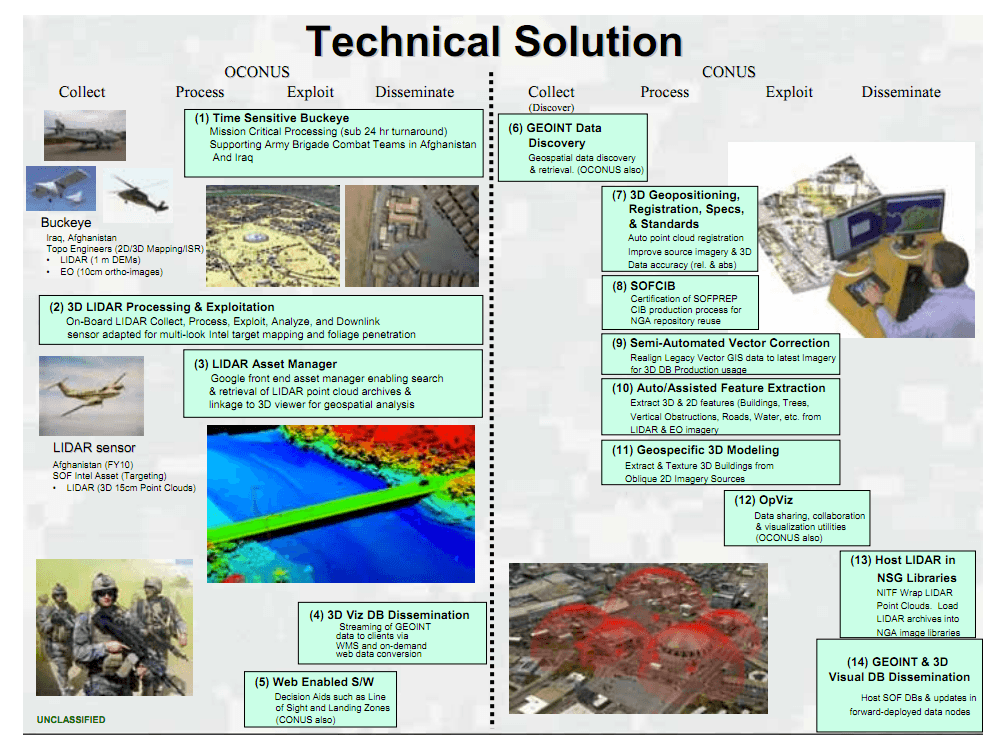

If you want to look at how they work all this data into their systems, I’ve got something there for you, too. I dug up this presentation from the ESRI User Conference last year, where Heidi Hainsey from the US Army Geospatial Center takes us through how the Army is integrating 3D data much faster into operations in Afghanistan so that the troops (or “warfighters,” which seems to be the term du jour) in the field can actually use the data relatively quickly after it’s been collected.

It’s definitely worth paging through. My favorite slide is the one to the left. That gives you a great idea of the complexity of the operations they’re conducting over there.

Of course, they’ve been using ground-based lidar since 2003, when they mobile mapped the Ring Road, involving the likes of Riegl, what’s now Terrapoint, Sony, and Honeywell. It’s an oldish case-study, but still well worth reading.

Basically, I think there would be a lot more room in the vehicle now, since everything has gotten so much smaller, and they’d be able to collect a lot more points and model faster, but in general I don’t think the work flow is all that different.

Unsurprisingly, lidar’s utility in Afghanistan is basically its utility everywhere: If gives you a fast 3D representation of the world around you, letting you make better decisions about your next course of action. In Afghanistan, the stakes might be higher, but the essential value proposition remains the same.

It’s not all peaches and cream, though. That GIF article does a good job of outlining lidar’s limitations, too:

1. If there are enemy aircraft in the area, you might get your lidar plane shot down. That would limit its effectiveness considerably.

2. If you’re in the wilds of Afghanistan/Iraq/wherever, your GPS coverage might not be the best. It could be hard to find a known point to use for callibration.

3. Lidar still produces huge datasets, and when you’re in the field you don’t always have the most advanced and high-powered processors to churn through all that data. Lag time isn’t friendly to mission-critical decisions. (This is where TerraGo’s 3D pdfs can be pretty handy, or Zebra’s printed out holograms.)

4. Lidar doesn’t yet populate automatically into all of the visualization and GIS tools that are out there, nor are there easy ways to fuse and correlate lidar data with multi- and hyper-spectral data. Point clouds kind of live out there on their own.

However, if the military can see the technology’s utility, you can bet that vendors can see the potential money to be made there. Or, as Buxbaum puts it, multi-sensor integration is going to happen sooner than later:

Industry is on an innovation path to provide a soldier or analyst the ability to produce an accurate 3-D model of terrain and buildings with geo-registered visualizations of video against this new 3-D data set, said Krakower. “And, this will all happen while the platform or UAV is still in the air,” he added.