The reality capture and digital twin spaces are in a really interesting time right now. In many ways, it’s unfair to refer to these tools and technologies as “buzzwords,” as there’s some implication within that term that they don’t provide real value. That’s certainly not true for either space, as countless firms and industries are leveraging both – often in concert – for tremendous ROI. At the same time, there are still debates about what the definitions of these terms even are, and many of the people and industries who could most benefit are still unclear of what exactly they need reality capture data and digital twins for, and why.

This snapshot in time brings us to this interesting point for the technologies, where broad awareness and knowledge are struggling to catch up with the massive growth around the respective spaces. Eventually, growth will slow down and this knowledge will catch up, but for now, it’s akin to chasing an unattainable carrot on a stick. And, according to Walter Lappert, it’s a time that is very similar to what we saw 10-15 years ago with drone mapping.

Lappert, who recently participated in a wide-ranging conversation with Geo Week News about reality capture and digital twins, is in a unique position to make a comparison between these technologies and drones. Today, he serves as the director of reality capture with Allen3D, a service provider for whom one of their main offerings is collecting reality capture data and helping create digital twins for their clients. His day-to-day job includes many conversations with clients who are often limited in knowledge about digital twins, and who need education about the value they can provide.

Prior to this, though, Lappert had extensive experience within the UAV space and saw the ballooning growth of that sector in the late aughts and early 2010s. Following his time in the U.S. military, he took his knowledge of drones and looked to make a career out of it. Ultimately, he did just that, starting a company that both built out the hardware for drone mapping as well as provided drone mapping services. In fact, that’s how he was first introduced to Allen and Company – Allen3D’s parent company – as he sold them their first laser drone system, which is still flown today.

Lappert spoke with Geo Week News about the conversations he has with his new clients, noting that there is often a significant amount of education necessary at the start. It’s something he experienced in his previous role.

“I kind of think of reality capture – which is what we call the indoor scanning – as exactly where I was 10 years ago with drones,” Lappert explained. “Drone was the keyword then; digital twin is the keyword now.”

When drone mapping was first getting off the ground, customers would often see examples of value peers had received from this technology and decide that it’s what they need as well, and the same thing is happening with digital twins today. There is some added complication to this, given the aforementioned lack of clarity around the definition, and Lappert talked through some of the steps that are taken from his end in working with customers who are looking to dive into this technology for the first time.

First and foremost, Lappert talks about what he and his team are talking about when they refer to digital twins. According to him, a digital twin is not just a 3D visualization, though that is often a component.

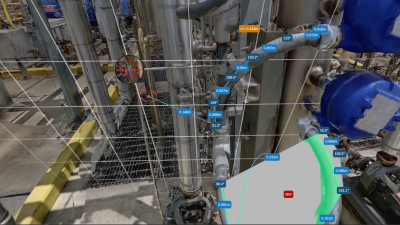

“To a lot of people, what a digital twin is just that 3D scan. To us, that’s not right; that’s just a visual representation. Yes, a digital twin has that scan, that reality capture component, but it has to have some other type of metadata or IoT connected to it to make a digital twin.”

Once that definition is established, the next step is figuring out exactly what that customer is looking for to determine the next steps. Lappert asks about what the digital twin will be used for, and how much scanning time will be allotted to create the basis for the twin, all of which can be used to determine what equipment is used for the reality capture. If sub-inch accuracy is needed, for example, terrestrial scanners will be required, which in turn means longer scan times and more expensive equipment. For other projects, however, a mobile scan can suffice.

“They think, Oh, just scan it. But you really need to find out the right tool to match their use case for the accuracy or fidelity of their project,” Lappert said. “That’s a lot of what my job is, is meeting with the client, understanding their real goal and what they’re trying to do, and then deploying the lowest cost, but still the best solution, for them.”

This, again, ties back to his experience in the drone industry, where similar types of conversations were needed, and similar education was necessary for new customers. When asked what similarities he finds between these two times, he immediately said that the conversations for both have to revolve around ROI. Customers can be excited about the technology – both last decade for drones and today for digital twins – but neither the providers like Lappert nor the clients are going to continue using the tools if there’s no return on what can be a substantial investment. That can often mean starting with a smaller project to show that value before moving on to bigger ones after the trust is established.

“I want the customer to see the value, get their return on investment, and then want me to go do the rest of their portfolio,” Lappert says. “Because now that they’ve realized that, I’m helping them make money. That’s where I relate it to drones - it was the same thing in the early days. Customers say they need a drone, but they don’t know what an orthomosaic or those kinds of things are; they just know that it’s a service we can offer. It’s the same with reality capture.”

.jpg.small.400x400.jpg)