While lidar as a technology has existed for decades, its use has often been in more niche applications and has mostly escaped much attention from mainstream technology news. When lidar was eyed as a potential solution for autonomous vehicles several years ago, suddenly, lidar started generating more buzz. This attention came as a result of startups and investors trying to predict, from a financial standpoint, which particular lidar technology would “solve” autonomous driving, but also expanded when projects that applied lidar for crowd monitoring and security began to evolve.

While the automotive industry remains mixed on whether lidar really is the keystone to the solution of fully self-driving vehicles (with many arguing that it will more likely be a combination of lidar, radar and imagery), there are still many, many more uses of lidar that I wish the mainstream news would take more notice of, and so many more just over the horizon, especially with the ongoing development and exploration of AI, machine learning and other edge computing and processing advances.

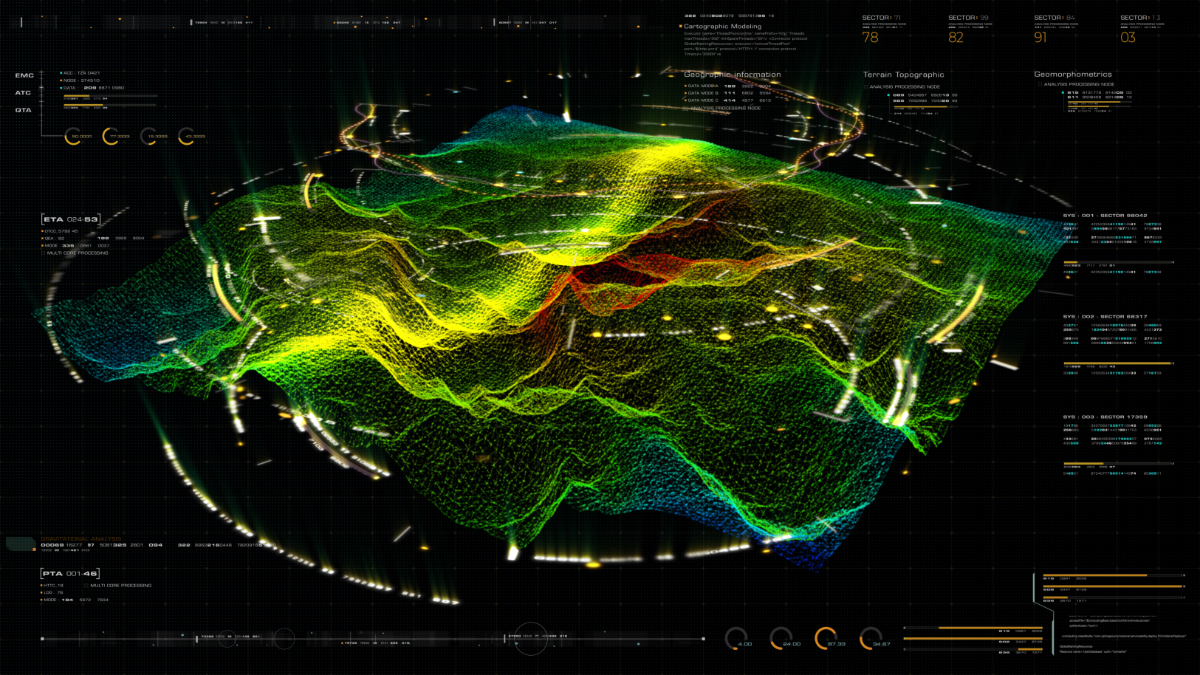

The biggest advances in lidar in the next few years will not necessarily come from the sensors, but from how the data is ultimately processed. The pain points of processing and the need for an expert to register, classify and clean up scans are on their way out - and this advanced processing can open up even new use cases - especially where short turn-around times are important.

Where it used to be impractical to spend multiple days in the field and then multiple additional days processing the data, we’re cutting down the time that’s needed on both ends. Registering and positioning scans is getting easier, both from updates to manufacturer software platforms as well as other 3rd party applications that are able to help bring scans from different devices together more seamlessly. On the capture end, the captures are getting quicker, and supplementing traditional scanning with handheld SLAM-based scanners can change the workflows from multi-day to multi-hour.

Other than reduced time on site, what do the combination of these advances get you? The ability to repeat scans more frequently. For some use cases, this isn’t necessary - when you’re just trying to get an image of a building façade to plan a renovation, for example. But what if you’re in an urban environment with 100+ year old brickwork throughout an entire city, and need to know if there are any new changes or cracks? What used to be a massive, multi-annual effort could be something that’s repeated yearly, or even quarterly, if needed. This could be used to target hotspots, or even look for bigger problems - is a section of your historical Main Street sinking, causing cracks? Or has there been an increase in vandalism in certain areas that lack streetlights? The questions that can be answered are only beginning to be explored.

The same could be applied to the natural environment. We’re getting to a level where we might be able to auto-classify trees by species using lidar scans, with highly accurate volume measurements. At Geo Week 2022, keynote speaker Chris Fisher pointed out that we might have been measuring carbon stores or commercial timber potential incorrectly by applying more generic or estimate measurements - and that there’s a real need to “archive the earth” to get closer to the truth. But if you could have details of a particular land parcel, you can not only revise those numbers to get closer to reality.

In ecological research, being able to use lidar to get a really detailed picture of a forest can yield new insights on succession, including how forests and other natural environments respond to disturbance from natural or human-caused disasters. By shortening the time between scans needing to process the data, field teams could sample more frequently, providing a detailed timeline of recovery.

But these are only the uses that are being built off of research or techniques already being done. What will we be able to measure or identify with lidar that we have never before, in the near future? Could repeated scans along coastlines or river banks over time give us early signs of erosion that we wouldn’t necessarily see with the naked eye? Can lidar classification of streets help us understand how urban spaces are working - or not working - for cars, delivery vehicles, pedestrians or people with disabilities? Can detailed scans of historical buildings unlock techniques and skills from antiquity that can be replicated today, or used for restoration (as we’ve seen in the Notre Dame Cathedral fire)?

These are just a few of the use cases that I can see around the horizon. What else is next?