At first blush, it wouldn’t seem there should be much, if any, overlap between the gaming and geospatial industries. As it turns out, however, gaming engines have proven to be a real boon for geospatial workflows, with growing collaboration between the unlikely bedfellows. This is something we covered last year in a conversation with Unity’s Rory Armes, who talked about how these engines were used in enterprise settings. Among other insights, he noted that decision-makers are increasingly coming from a generation that grew up with video games and they’ve demanded that level of quality when rendering data in their work life. The pairing has continued to flourish in the time since that conversation, and more stakeholders are taking advantage.

There’s perhaps no greater proof of the value these engines can have in the geospatial industry specifically than the participation of Esri in making these connections. In 2022, the leading GIS company introduced ArcGIS Map SDKs for both the Unity and Unreal gaming engines, and progress has continued since that announcement. Recently, Rex Hansen, a product manager with Esri, spoke at NVIDIA’s GTC conference in a session entitled Turning Real-World Data into Geospatial XR Experiences with Esri ArcGIS and NVIDIA CloudXR, talking about how beneficial the combination of GIS, gaming engines, and mixed reality can be for geospatial work. Hansen later spoke with Geo Week News to delve further into the subject.

With over two decades of experience in the GIS industry, Hansen has a unique perspective on how this relationship between geospatial and gaming engines came to be, as well as the eventual implementation of mixed reality. He points to a period about 15 years ago, when gaming engines were still used almost entirely for entertainment, as the point at which some folks were beginning to recognize the benefits of game engines. However, the geospatial software providers didn’t necessarily catch up in time, and they instead saw professionals taking matters into their own hands.

“What we found in game engines, as they’ve been able to advance over the years, we’ve seen a few really grow and provide this flexible, rich system architecture that allowed for the introduction of physics engines, particle systems, special effects, animation, etc., and our customers wanted to take advantage of it,” Hansen says. “What they were doing, I’d say about eight to ten years ago, was they were taking their real-world data out of ArcGIS and putting it into some other format – there’s a variety of 3D formats – and they were trying to bring it into a game engine so they could take advantage all of the benefits these systems provided.”

This proved those in the industry saw value in these workflows, but its ad hoc nature was obviously not ideal for anyone involved. Esri believed they were in an ideal position to address these needs from industry insiders, which only continued to grow with the advent of mixed reality workflows. Ultimately, they released the aforementioned SDKs as a public beta in 2020, and Hansen tells Geo Week News it was the company’s most popular developer beta with about 7000 users, and the second most popular beta program they had through their early adopter site after only the Field Maps public beta.

Fast-forwarding to today, there are still plenty of professionals who are just starting with these game engine-enabled workflows, and Hansen says they generally fall into two buckets. The first is companies who have experience in the GIS world but are new to the 3D rendering space, and they’re primarily concerned with things like the investment required to use a game engine to bring lifelike realism to their 3D GIS and the ability to maintain precision of geospatial data as well as the accuracy in mixed reality. On the other side of the coin, companies with experience on the 3D rendering side but less so on the geospatial side are primarily concerned with things like having access to real-world data, how to manipulate geospatial data, and the required investment.

That said, Hansen makes sure to note that these lists are not necessarily mutually exclusive but rather just prioritized. “Organizations with experience in GIS also want to manipulate geospatial data. Likewise, organizations with little-to-no experience in GIS are concerned about accurate representations of digital content in world-scale AR experiences.”

As one can imagine given the diversity in Esri’s customer base, Hansen relays a number of different use cases enabled by this combination of geospatial data and gaming engines, and even in the way that it’s used. There is capability for users to visualize their data in both mixed reality and desktop settings, though Hansen notes that in their beta program 70 percent of the 7000 users indicated they “intended to build an XR experience.” Intentions are, of course, not always indicative of what will actually happen, but that’s still a substantial share.

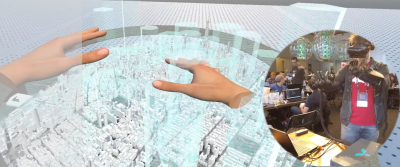

Looking at the mixed reality work more specifically, Hansen highlights a number of different ways this is being used by his customers. With augmented reality, for example, he points to built world work being the best fit, providing the ability to do things like visualize new assets in an existing building or locating infrastructure that may be hidden behind a wall. With mixed reality, which allows users to interact with both digital and physical elements simultaneously, he looks at work that was once done with physical maps on a tabletop turning digital, allowing for more immersive planning that can even be done collaboratively in remote settings. Finally, with full virtual reality, Hansen points to urban planners as one example of stakeholders who benefit, being able to do things like visualize and review planned structures in spatial context before construction.

Although there are already plenty of proven workflows with these advanced visualizations, Hansen sees more coming down the line. In terms of next steps, he points to visual positioning systems being better leveraged, more readily available 3D geospatial data, improvements in AI powering things like extrapolating GIS attributes and simulations, and ultimately a more connected industrial metaverse.

To that last point, he notes that current work in that space focuses on “design and manipulation of assets in relative coordinate space.” However, he says, “at some point when those assets need to be represented in the real-world, in absolute coordinate space, the use of real-world data for context and calculation will be important.”

Overall, it’s hard not to be excited about where things are headed in this space. “Having just gotten back from GTC and seeing the significant focus on XR and just digital twins,” Hansen says, “the buzzwords have meaning, because they translate into something real. Whether it’s an industrial metaverse or a living digital twin, or it’s XR, all of it really is a factor and they’re putting their money where their mouth is, which is great. We like to see that come to life.”