End users of geospatial hardware and software, me included, can be a curious lot. We yearn to know more about how these seemingly magic solutions work. This includes learning more about the thought processes of designing these things. This is especially important in process automation, operation simplification, and what is essentially a transition from legacy discrete data point capture methods to mass data capture. Knowing how things work can help instill confidence in the quality of the data deluge from these highly automated solutions.

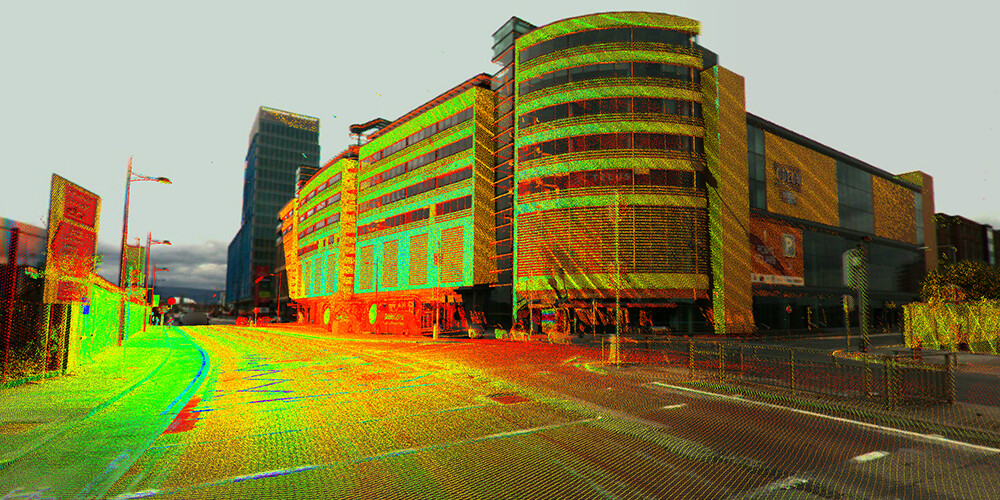

Broader adoption of mass data reality capture technology is becoming imperative. Mobile mapping, UAV mapping, handhelds, scanning total stations, and backpack systems. How else can visions of digital twins, smart design, BIM, and (useful) metaverses be realised? Legacy methods and solutions will never be able to keep up.

Presently, reality capture solutions encompass many key aspects of disruptive innovation in the geospatial sector. Recently, I set out to examine various elements of the design process for such solutions. When I ask geospatial manufacturers about specific technologies, I am often handed off to a marketing specialist. While they may be versed in technology, what I really want is to speak to an engineer. I was pleased when Hexagon recently connected me with a design engineer and a product specialist. I’m not endorsing any specific products, as there is a wealth of great options out there. However, I have to thank Hexagon for being so open about their design process.

To better understand what goes into these “mystery boxes”, the topics for discussion focused on how much user feedback, and lessons learned from preceding products, inform the development and design process. But even more so about how process simplification is pursued. The topic of “simplicity” evokes different views; one of productivity gains, and another of caution. Many geospatial practitioners fear that hardware and software are becoming too simple in some ways. They fear the predominance of “black boxes”, and “button pushers”. I do not share such fears; those buttons bring tremendous productivity gains, provided proper care and diligence are exercised.

The Front Line

“It is important for us to experience the challenges of our users firsthand to find the right solutions,” said Matthias Wieser, VP Industrial & UI Design at Hexagon’s Geosystems division. “Before COVID, we used to travel a lot. This means product management was also involved in demos, sometimes closing sales. And if the competition was tight, we were facing product “shootouts”. You are on the spot; you have to do a survey and prove that your system is better.” Such immersion in the customer experience has resumed, and Wieser said it is beneficial as they can experience firsthand any pain the customer is feeling. Other channels for feedback are regularly employed, including customer polls, and dealer input.

However, it may not always be prudent to rely solely on customer feedback, as the customer might not be aware of emerging technologies that could be applied. “It is balance. We may solicit generic feedback, asking their opinions on various topics,” said Wieser. “Will they buy it again? And if not, what improvements would have made the difference?” Customers may not want every function automated; they may still want or need to control various aspects of the process; at least until they are more comfortable with such rapid advances in automation. “It’s like being on a highway; you have guardrails to help avoid going off the road, but you still need to be able to drive,” said Wieser. “And that’s the difficult spot, finding the balance and having the eyes and ears to see and listen properly.”

Applying Lessons Learned

As an example, I asked about the design process for the Leica Pegasus TRK mobile mapping system that I recently wrote about. What elements of user feedback heavily influenced the design of the TRK systems?

“We started by examining the whole operation of a mobile mapping system, from the first step, setting up a system,” said Alessandro Nuzzo, Director UX, Hexagon's Geosystems Reality Capture division. “We realised that the older systems were too heavy. Customers have noted this, and we saw that often during demos, we had to request help from potential customers to lift and mount the system. That was painful, because they already saw lighter systems on the market, that did not perform as well, but were lighter and easier to install. That was a big consideration for customers wanting to send one-person mobile mapping crews out. A tough decision to perhaps compromise a bit on performance, to balance that with operational practicality.”

Nuzzo said that customers were very happy with the performance of the legacy systems, but that the appearance was clunky and needed to be more modern. It may seem odd that appearance should be a factor, but perception can mean a lot. Fortunately, technological improvements were incorporated into the smaller and more streamlined design, like the GNSS antenna built into the body of the system, and modular mounts for standard and optional cameras.

“Once you think you have enough information, the fun part starts,” said Wieser. “It is becoming creative and having your own interpretation of how to solve certain issues. And then you go inside the technological aspects: How can it be solved? What can be further automated? Is there a potential AI workflow? Is there an upcoming technology within Hexagon that can be leveraged? Examining the entire workflow can be quite complex; this can require a lot of time.” Nuzzo said that the design process that became the TRK began six years ago.

Simplicity and Dominant Design

People are so used to simplicity in the technology of their daily lives, the tolerance for legacy geospatial solutions has worn thin. “One of our primary areas of special focus in design is a fluid pairing of software and hardware. We are all used to apps in our daily lives that mostly work flawlessly, our cars are smarter, our appliances—we should expect the same in reality capture solutions.”

“Then you enter in the concept of dominant design. Like if you are on a website, the navigation menus are very similar across the industry simply because there is a dominant design,” said Wieser. “The same applies to a professional system, they are expecting it to be as easy to use as modern apps on an iPhone or an iPad, and that is the feedback we're receiving.” I can attest to being relieved that the old 1200 Series system for Leica Geosystems surveying instruments was replaced. Outstanding in its depth and capabilities, the replacement Leica Viva series, and present Leica Captivate software are much more intuitive, and can be operated with much of the ease of consumer apps.

However, unlike consumer apps, there has to be a depth in end-use specifics and no compromise of results—shortcuts without shortcutting quality. “In terms of accuracy, you can never be accurate enough for surveyors, you start including different technology to improve the accuracy without making it more difficult to operate,” said Wieser. “For example, in a mobile mapping system, you integrate newer, multi-constellation GNSS receivers with greater processing power, you add SLAM scanners to improve position stability and for GNSS limited areas. You start evaluating different elements to tweak the last bits of performance from them, etc., as we have for the TRK. But all that needs to be packaged with a great user experience, or UX.”

Industrial design meets improved UX. Users may ask for more features, but it is crucial that they tell you what the problem is they hope to solve. There is a threshold for this. Simply piling on new features can contaminate the user interface, and workflows can blow up. For new users, this can backfire as they get lost in complexity. This is the balance that Wieser and Nuzzo speak of.

“Often, people confuse abundance with choice,” said Nuzzo. “Simplicity is, for me, a catalyst that forces you to make choices; to understand what you want, and what you don't. “I would say in the past, a lot of product development was technology-driven,” said Wieser. And at the time, that was probably right. But nowadays, we want to focus on the solution: How can we solve the user’s problems? And how can our technology help to find a solution? I see a shift from technology-driven to more solution driven, but to satisfy the actual needs of the user.”

There are end users that want to know and analyze every aspect of the technology, sometimes to the point of overthinking it, and hesitating to use it (while others adopt and gain competitive advantages). One of the goals of simplicity is to expand to broader groups of users, groups that may not be so concerned with the details; they may only want “the pill that will cure their headaches”.

Puristic, Intuitive, and Iconic

Clayton Christensen was an American academic and business consultant best known for his theories on disruptive innovation. He cautioned big companies against “becoming too good at what they do”. Resting on laurels is hazardous for a business; companies need to keep innovating. There is a lot of great innovation going on in the geospatial sector and especially now in reality capture. Evolving tech can be a moving target, however, there is a lot to be gained from continuity in certain aspects.

Nuzzo said that regarding mobile mapping, Hexagon began with mobile systems (with traditional scanners), then into backpacks where SLAM was introduced. The experiences with these have contributed to the Pegasus TRK system. While there has been some product name continuity and common hardware/software elements along the way, the Pegasus TRK may be the inflection point in Hexagon mobile mapping that leads to a continuum of product design, like the BLK line of scanning/imaging products.

“When we speak of BLK, that is the very example of disruptive innovation,” said Wieser. “It makes a product so much affordable, easy to use, and accessible to a much larger population of users.” BLK products like the Leica BLK360 imaging laser scanner, Leica BLK2GO handheld mobile scanner, Leica BLK2FLY (flying laser scanner), etc., should not be compared to a large format terrestrial laser scanner like a ScanStation P50 in terms of range, density or precision—the BLK line fits a sweet spot for a broader range of applications.

Without drilling too deep into the details of the various BLK products, I wanted to know more about the design aspects. “The BLK line has one tagline: ‘Reality Capture Made Simple’. And simplicity, in this case, also means being very efficient. If something is simple and intuitive, you'll be quite efficient. We wanted the design to reflect this, from the operation to the form factor.”

Wieser said the BLK has its own design language, down to the colour, look, and feel. The design alone conveys the idea that if you can operate one BLK product, you could operate any of the others (which is essentially true). There was a design goal to centre the operation of the hardware with a single button, while the finer operational elements are handled in simple apps. Initial applications envisioned for the original BLK360 included architecture and BIM, where a broader group of users could operate it.

User experiences with the first generation BLK360 were key in developing the latest version, said Wieser. For example, a data port was added, rather than relying solely on wireless data transfer. The size was reduced, and a better camera was added. Another aspect of the BLK design is what Wieser calls “puristic”. “Puristic means, from my perspective, to reduce to the max. Everything that is not needed, everything we can take away and boil it down to the very essential. Let's say shape elements and function elements that are actually needed. That's to create clarity. For the BLK, that is a simple shape and other design elements like colour, button, lights, and no need for additional boxes.”

Often, lateral technologies are developed for other products that get integrated into lines like BLK. For example, there was a technology now called VIS, which Wieser said was developed to determine scanning positions from station to station to immediately combine and visualise captured data without manual intervention. It was implemented on the Leica RTC360 terrestrial laser scanner. Elements of this R&D were integrated into the GrandSLAM tech in the BLK2GO. It combines LiDAR SLAM, visual SLAM, and IMU for seamless handheld scanning. Whatever the tech inside and how it evolves, it is unmistakably BLK.

An Unburdening

From talking with Wieser and Nuzzo, I gather that their take on the end result of simplification is not just fully automated “button” solutions. Instead, the critical goal is to increase productivity without compromising quality while injecting the user appropriately into the process. Too many decision points can burden the user. You input parameters and presets to govern the quality you require, then when the process needs your expert judgment, the system should be smart enough to prompt you. You need to be involved with the system design from the start and understand its strengths and weaknesses to really use it properly.

It was only a few years ago when high-end mobile mapping systems broke the centimeter precision barrier, which still involved setting many control targets. With systems like the Pegasus TRK, centimeter precision is achieved with far less control (I looked at data from some early adopters). High productivity precision while being much simpler to operate. Yes, someone (plus a little AI tech) needs to process and extract data. But if the mundane elements of reality capture can be reduced without compromising quality, then geospatial practitioners can apply their skills more productively.