The search for and discovery of remains from prehistoric organisms has captured the imagination of humanity dating back to ancient times and continuing into today. Whether it’s a mild interest in dinosaurs as a child or something one turns into a career as a paleontologist searching the Earth for fossils, people of all ages have taken varying levels of interest in this field. What may be surprising, though, is that the current methodology for tracking and storing data related to these findings is not as sophisticated as one might immediately assume. As more technological solutions from other industries start to popularize more broadly, though, that is starting to change.

An engine behind potentially changing this in the paleontological realm is Tom Hebert, a former insurance business owner who discovered his love for paleontology later in life. He now chases this passion on a full-time basis, finishing up a degree at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, and developing a new GIS-based solution to organize and map data regarding discoveries. Hebert recently spoke with Geo Week News to share the story of how he left the insurance realm for paleontology, how he’s starting to implement GIS tools into this work, and how he’s using his newfound expertise to inspire children and adults alike.

Finding a new path

Hebert never expected to get into paleontology to any degree, never mind it becoming his entire professional life, telling Geo Week News that he got into it “completely by accident.” He had been spending time with his daughters after a divorce, and told them each could have an entire weekend in the summer to do whatever they wanted. His oldest, Samantha, requested a trip to Country Fest, and then it was time for his youngest, Emma, to choose.

“I’m like, Come on, Hawaii. Come on, Europe,” Hebert said. “And she’s like, I want to go dig for dinosaurs.”

That decision ultimately set Hebert down a new path which he continues to travel today, even as the interest has passed Emma by. Hebert searched for places where they could dig for dinosaurs, finding a location in South Dakota, and he immediately got hooked.

“For someone like me that’s very much an A-Plus personality, always on the go, not always the best example of patience in this world, there was something absolutely cathartic about being out there.”

After that first trip, it became an annual expedition west to South Dakota, with the trips getting progressively longer, until the owner offered Hebert a job as a summer tour guide. Then, about four years ago, he decided it was time for him to sell his insurance business, go back to school, and dedicate the rest of his professional life to paleontology and dinosaurs.

He enrolled in the geography department at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, and this is where the idea of his GIS-enabled solution for paleontology was born.

Mapping new discoveries

Coming from the insurance industry, Hebert tells Geo Week News that he had been familiar with GIS prior to this shift of career paths, as this was part of tracking properties. And so when he was in a GIS class, his professor was talking about all of it and his idea clicked.

“I raise my hand up and say, So, I could do this to map dinosaur bones? She’s like, You could use this to map just about anything you want. I went to the chair of my department and said, Do you know any other students that might be interested in a little side project to maybe help me out with this? I want to map out our dig sites using a GIS program. He said, Oh, this is a research project.”

Hebert was then sent to try and find funding and equipment from the university to assist him, which ended up being a challenge. Understandably, the university was hesitant to hand upwards of $30,000 worth of surveying equipment to a student with no experience using it across state lines, so he had to shift his strategy. He began reaching out to individual companies asking for help in exchange for some good PR, and after being ignored or rejected by everyone, he heard back from Carlson Software.

Working with Ladd Nelson, a sales rep from the company, Hebert outlined what he was hoping to do to get accurate positional data of dig sites, and Nelson provided “$40-50,000 worth of equipment,” including their BRx7 receivers. Hebert and two other students went out to South Dakota to begin this work, and he has since presented on this at conferences to spread the word of how this all works.

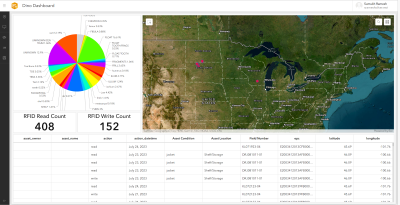

Within this system, he is able to store a plethora of data pinned to a highly accurate position on a map, storing things like location, owner, species, anatomical location, morphology, and condition. More recently, they’ve started to use X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) to collect chemical composition of their findings, which can in turn help provide a helpful estimate for a dinosaur’s age.

This is still a relatively new system, though, and has not caught on among the wider paleontology space to this point. Right now, Hebert says, “the biggest concern or pushback we get is in the academic world, because they’re very concerned about protecting the integrity of their sites.”

It’s a concern they’re starting to work to address. He told Geo Week News that they are testing new systems using RFID and NFC technologies to tag fossils. “So if you have a smartphone, you can literally walk up and scan the tag, and we’ll give you all the information we’re going to allow you to access,” Hebert said.

Asked about why this kind of system hadn’t existed before, he said, “As with anything, change is hard, and adding in technology to field sciences like paleontology and archeology can be even harder. We grow very accustomed to our processes and procedures for doing things and sometimes we stop looking for a different, faster, or better way.” He also noted the costs associated with acquiring the equipment to tag this, which can certainly be a burden.

Passing on the paleontology bug

In addition to his GIS work, Hebert has since founded the Earth Sciences Foundation, for which he also acts as the director. This is a nonprofit organization whose mission, per their website, “is to make the world of Earth Sciences available to everyone.” And as he explains to Geo Week News, this includes groups of both children and adults.

The foundation has three main programs for their work, starting with their youth outreach program. This allows kids to get excited about Earth sciences, providing a path to entering these fields as they grow older and potentially study them. Hebert says they’ve worked with children as young as four – though that was somewhat extenuating circumstances – and most often works within the eight to 15 year old age range. He said, “We’re getting more and more high school students, juniors and seniors are getting involved. We’re getting more and more opportunities to start working with universities and getting more internships developed as well.”

He continued, “I wanted to create some place where students could come to me with crazy ideas and we’ll say, Let’s give it a shot.” He said this kind of work can get kids involved in these fields later in life. “This is how we get kids into science. This is how to get them into GIS, into land surveying. We can use the platform to get younger people to start looking at geospatial and land surveying careers.”

Those ideals aren’t limited to working with children, either. Hebert’s nonprofit also works with veterans coming back from combat for what he calls “decompression digs.” He takes these opportunities to show how they can use their experience in the military and translate that into careers in Earth sciences, geospatial, and land surveying, finding space in industries with massive demand.

Finally, he also spoke about his work with local Native American communities, looking to get young people and other members of this community involved in the work.

“Right now, we’ve got plans drawn up for a 200,000 square foot museum we’re going to be building out in North Dakota in the next few years,” Hebert said. “We’re getting a curriculum introduced to the university to include paleontology, geology, land surveying, GIS, map-making, all stuff that they haven’t been exposed to before or even knew was an opportunity.”

All of this has come from a weekend with his daughters, sparking a life-long love and a passion to not only find dinosaurs, but share that experience and open up a new world both to those already in the industry and those outside of it.

“You realize you’re the first person that’s ever held that in its entire life. No matter where you came from, no matter what’s going on in your life, no matter where you go from here, nobody can ever take that away from you. It doesn’t matter where that fossil ends up, your name’s on it. You’re the one that found it, and it’s just the coolest experience ever for me to have that experience myself, but also be able to share it with other people and take them out.”