According to a recent publication in Optica, researchers working under Laura Waller at UC Berkeley have developed an “easy-to-build camera that produces 3D images from a single 2D image without any lenses.” The “DiffuserCam” can capture high-definition 3D information in large volume without the use of a scanning mechanism or difficult-to-manufacture micro-circuitry.

The camera hardware is much simpler than you might imagine, even given the above description. It’s “essentially a bumpy piece of plastic” that is “placed on top of an image sensor,” a summary article explains. This simplicity makes it versatile and easy to construct. To wit, researchers in Waller’s lab say they can build it using any image sensor, and practically any bumpy piece of plastic, including privacy glass stickers, Scotch tape, and conference pass holders.

Despite the DIY approach, the DiffuserCam is no joke, as the camera can reconstruct 100 million voxels (points in 3D space) from an 1.3-megapixel image. As a comparison, the article mentions that the new iPhone X captures 12-megapixel photos. My amateur napkin-based math estimates that you could use that image sensor to build a a DiffuserCam that captures more than a billion points.

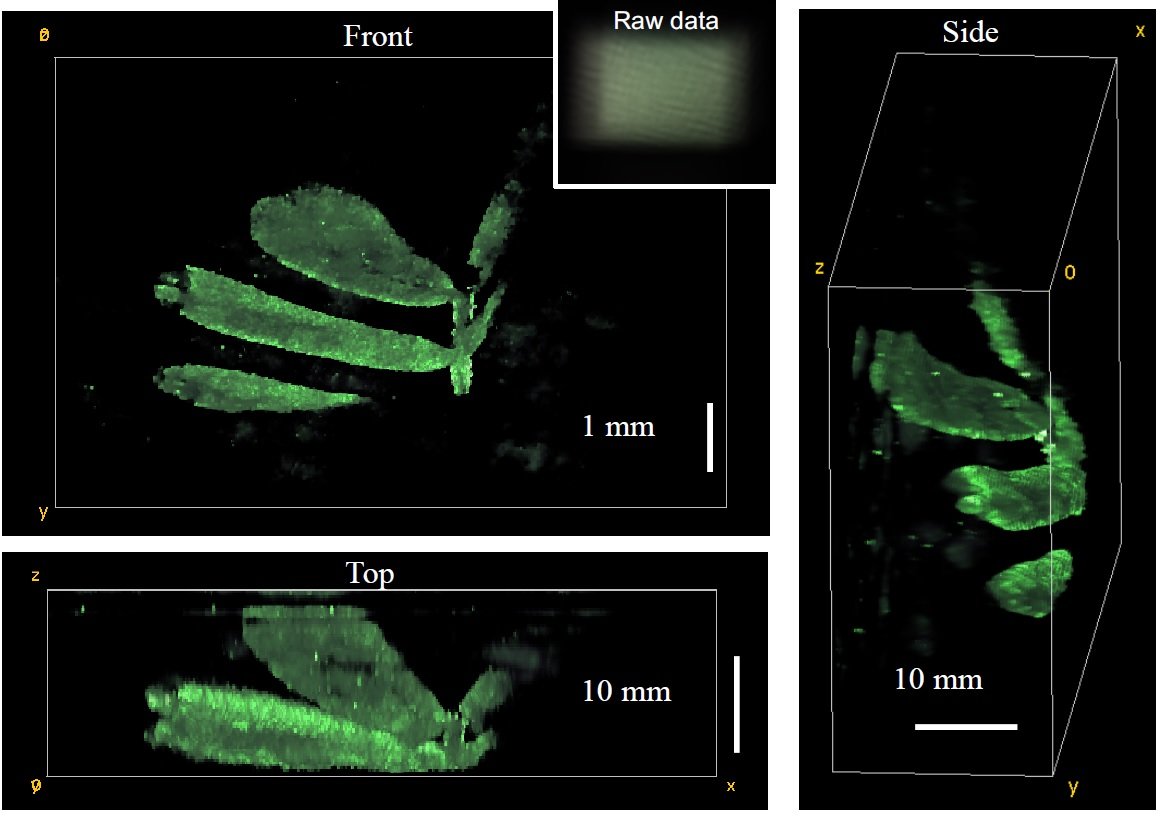

Waller says it can image objects close to the sensor at a resolution of about 10 microns, though the resolution drops as the objects get farther away. It can’t decrease /that much/, though, because Waller’s lab has used it to capture the 3D structure of plant leaves, she imagines it could be used for self-driving cars, or with machine-learning algorithms to perform face-detection, people tracking, or object classification.

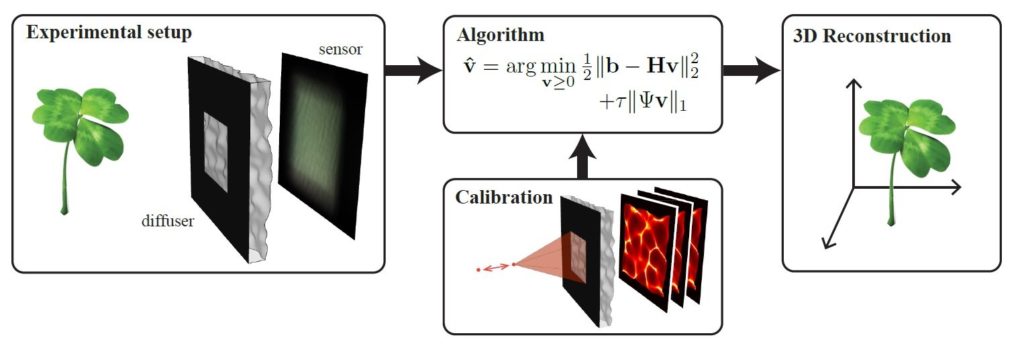

But, you ask, How does it work? The magic lies in Waller’s use of “computational imaging,” which is “an approach that examines how hardware and software can be used together to design imaging systems.”

In other words, the hardware and software are thought of as two smaller, complementary parts of a holistic imaging system.

This approach enables the researchers to unload the complexity off of the hardware and into the processing algorithms. This proves the old adage that “software eats hardware,” and brings with it one of the classic benefits of code: You only have to make the complex software once, because after that it can be easily copied and distributed.

The lensless DiffuserCam consists of a diffuser placed in front of a sensor (bumpson the diffuser are exaggerated for illustration). The system turns a 3-D scene into a 2-D image on the sensor. After a one-time calibration, an algorithm is used to reconstruct 3-D images computationally. The result is a 3-D image reconstructed from a single 2-D measurement. Credit: Laura Waller, University of California, Berkeley

Waller says this combination of simple hardware and smart software even allows “others to create this type of camera at home.”

That means that anyone with an image sensor, a piece of plastic, and thew means to copy and run an image-processing software solution can have a 3D sensor. As such, the camera opens up a whole range of new uses into play for 3D capture—so many, in fact, they make last year’s headlines about the “democratization” of 3D sensors seem quaint by comparison.

Here’s one. The researchers plan to use the DiffuserCam to capture the firing of mouse neurons. “Because the camera is lightweight and requires no microscope or objective lens,” the Optical Society writes, “it can be attached to a transparent window in a mouse’s skull, allowing neuronal activity to be linked with behavior.”

Waller says her team’s work proves out the usefulness of computational imaging, showing that this holistic approach enables breakthroughs in performance and price that were not possible before. Still, she warns, “this is a very powerful direction for imaging, but requires designers with optical and physics expertise as well as computational knowledge.”

Maybe that’s one of you?